See also the pages

Review of 50+ Heaney poems

Heaney: ethical depth?

Heaney: translations and versions

[Heaney's translations and my own translations]

Heaney's

'Human Chain'

Heaney's poetry: the case against and the

'Harvard Connection,' with

general and specific criticism of Harvard University

Seamus Heaney and bullfighting

Ireland, Northern Ireland:

distortions, illusions

Metaphor

Metre

Above, a Greek donkey, overburdened, like the donkey described below, but with a very different, distinctly modern load, including computer monitors. I've chosen this section to introduce the material on this page, not the general Introduction, which is the next section.

The references and allusions in Seamus Heaney's poetry offer so many opportunities to commentators with specialist knowledge, such as Bernard O' Donoghue, the editor of the Cambridge Companion.

Seamus Heaney has overloaded his poetry so much that it resembles a donkey carrying an immense load, staggering along 'Greek roads ... 'looped like boustrophedon ... i.e. like that ancient reading or writing style that alternates direction on every line, the word itself meaning 'turning like an ox while ploughing,' ' [all quotations in this paragraph are taken from The Cambridge Companion], he has piled it high with 'Old Norse and Old English literary traditions,' including 'Old Icelandic family sagas' and 'an Anglo-Saxon philological past,' has loaded it even higher with 'The Latin and Greek classics ... a constant presence ... throughout his writing lifetime: Hercules and Antaeus, Sophocles' Philoctetes and Antigone, Aeschylus' Agamemnon, the Virgilian Golden Bough, Narcissus, Hermes, more recently Horace' (after a period in which he avoided 'the Theocritan-Horatian-Virgilian bucolic'), Virgil's Eclogue iv ('Heaney explained to Cavalho Homem that the connection with Eclogue iv was the pregnancy of his niece, particularly in the half-line 'casta fave Lucina ...' ), other Eclogues ('The clinching reference connecting Heaney's eclogues with Virgil's Eclogues i and ix then follows: the Synge word 'stranger' followed by an italicized quotation'), not forgetting 'the Horatian metal (an unlaboured aere perennius) of the implements in the translation from Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin and in the hopeful millennial anvil linked to it,' not to mention other weighty allusions, allusions to Dante (as when 'Charon replaces Hermes'), allusions to Roman Catholic rites, customs or piety, such as the breviary, soutane, scapulars, church-latin, allusions to both of these at once, such as 'a Dante-influenced pilgrimage to Lough Derg in County Donegal, a demanding penitential programme ...'

Reading some of the poetry of Seamus Heaney and some of the contributors to The Cambridge Companion can seem a demanding penitential programme.

I'm well placed to understand many of the references here, although not the references to Old Norse, Old English and Old Icelandic matters. I've read Virgil and Horace in Latin and I've read all the extant Greek tragedies in either English or Greek, including Aeschylus and Sophocles. I'm well placed to understand the Catholic allusions in Seamus Heaney's poetry, with commitments in the field of counter-evangelism, anti-Catholic as well as anti-Protestant. I comment on translation of Dante, including Seamus Heaney's, in my page Heaney Translations, where I provide my own translations from Italian, Latin, Greek and other languages. But I question the use of these references on such a scale. See also my short section knowledge and learning in the poetry of Seamus Heaney.

It would be very mistaken to view Seamus Heaney as a poet-scholar. His erudition and learning were subject to severe {restriction}. I provide evidence in my pages on the poet. For example, he was under the impression that the fighting at Ypres in the First World War took place in France, not Belgium, as I point out in my commentary on his poem Francis Ledwidge. This is ignorance about one of the major areas of fighting, where Francis Ledwidge was killed. Seamus Heaney thought that Wordsworth was skating on Windermere not Esthwaite Water in the episode in 'The Prelude:' Wordsworth's Skates. It would have been worth mentioning these mistakes in the Cambridge Companion but perhaps the Editor and none of the other contributors detected them.

Amongst the associations of the Cambridge name - better not to refer to the Cambridge 'brand' - are associations to do with excellence. 'The Cambridge Companion to Seamus Heaney' is hardly ever excellent. Instead, the good, the not-so-bad, the bad and the shockingly bad.

In the Acknowledgements section, the editor, Bernard O' Donoghue writes, 'My primary thanks are to Seamus Heaney, for providing the incomparable subject-matter and for his hallmark generosity and goodwill towards the project.' 'Incomparable' is a glowing term of approval. Was such a cosy relationship between poet and project healthy? Was there any difficulty in maintaining critical independence and applying proper critical standards when the poet showed such 'generosity and goodwill towards the project?'

So much in The Cambridge Companion is irrelevant for a critical, fair-minded view of Seamus Heaney's poetry. The Companion is sometimes good at recording. A 'companion' should offer background information which is useful and interesting, and some of the information in the book is genuinely useful and interesting. But H D F Kitto, a scholarly critic from a previous generation, wrote in 'Greek Tragedy:' 'We observe that during this period certain developments occurred in what we call the Greek tragic form. We record them - a rational thing to do, certainly, but it is not criticism, and if we are not careful it may impede criticism, that is, understanding.'

Overall, the Companion was a missed opportunity. It gives a bare mention of some of the accumulated misgivings and outright criticisms of his work but doesn't examine the poetry in detail, in the light of informed criticism.

So, Dennis O' Driscoll gives the information that 'North,' widely regarded, and in the opinion of Dennis O' Driscoll rightly too, as 'Heaney's finest and most original collection' was 'greeted with a virtually unanimous vote of no confidence in his native Ulster.' And, 'One of the reviews of North, by Ciaran Carson in the Honest Ulsterman, has been endlessly quoted as a representation of the case against 'the Bog Poems', as they were called from the first. According to Carson, Heaney had laid himself open to the charge (in fact Carson did not literally level it himself) of being 'the laureate of violence - a mythmaker, an anthropologist of ritual killing ... the world of megalithic doorways and charming noble barbarity.'

If it was beyond the scope of his chapter to examine such an important collection in some detail, to give some of its poems a close reading, to examine the arguments against in detail, then it ought to have been done in another chapter. On the same page, there's the statement, 'the poems ('Whatever You Say Say Nothing', for instance) which are explicitly political or topical in theme are less frequently successful, and several such poems remain uncollected.' This needed further explanation, but didn't receive it. Appearing in a collection isn't necessarily a guide to quality. I point out that 'Gifts of Rain' made it into the 'New Selected Poems 1966 - 1987' despite its poorness, and I explain why I think the poem is poor.

Seamus Heaney emerges from the generalities in so much of 'The Cambridge Companion to Seamus Heaney' and the scholarship, or a form of scholarship (useful and interesting but almost always with no critical importance) with reputation essentially intact. He emerges from extended close reading with reputation confirmed in some ways but in significant ways severely reduced.

Bernard O' Donoghue's deficiencies as an editor can be appreciated by comparing him with a very good editor such as Peter France, the editor of 'The Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation.' The Guide doesn't contain very detailed discussion and couldn't be expected to. It's a survey of a vast field, but a very interesting survey. He writes in his Introduction, 'Where translations are compared, there has been no attempt to impose neutral description rather than critical evaluation. Nor is there any party line here. Contributors have been discouraged from grinding their own axes too loudly, but have felt free to offer judgments. This is a guide, after all, and anyone offering guidance will be concerned not only with the nature of existing translations but with what is perceived as the success or failure with which different (often equally valid) translation projects have been executed.'

For more on Dennis O' Driscoll, see my page 'Surveys:' the section on literary criticism and sampling.

His distinction as a writer doesn't include his contribution to the Cambridge Companion. This is an example of mindlessness from Dennis O' Driscoll in The Cambridge Companion, aided and abetted by the editor. From my discussion of Gifts of Rain (Wintering Out):

'The claims made for Seamus Heaney are often very radical, not including the power of miraculous healing but including miraculous gifts of language and in the world of ideas. Dennis O' Driscoll, in 'Heaney in Public,' one of the essays in The Cambridge Companion, claims that 'Every idea is examined afresh, as every word is coined anew.' Every idea is examined afresh! Every word is coined anew! Are all these five words in 'Gifts of Rain,' 'could monitor the usual / confabulations' coined anew? Bernard O' Donoghue ought to have had a few words with Dennis O' Driscoll and made it clear that this claim couldn't possibly be justified and shouldn't appear in any self-respecting book, and certainly not one published by the Cambridge University Press. The Press had its reputation to consider, and so did he, as editor, and as an academic at Wadham College, Oxford.

But he obviously didn't even notice that Dennis O' Driscoll was practising a form of 'automatic writing.' He was practising 'automatic editing.' In the 'Acknowledgements' section he writes, 'I have drawn on Dennis O' Driscoll's noted infallibility more than once.'

In the same section, he thanks two people for help with word-processing. 'Without them, the book would have never reached its quietus.' 'Quietus means 'a release from life; death,' from the Latin 'quietus est,' 'he is at rest,' as Bernard O' Donoghue the Latinist should know.

'Dennis O' Driscoll's claim is 'falsified' very quickly, with a quotation from Seamus Heaney just a few lines later, one without any freshness or originality in wording or in the idea: 'no poetry worth its salt is unconcerned with the world it answers for and sometimes answers to.' (This quotation comes from 'The Peace of the Word' in 'The Sunday Times Culture Supplement.')'

Dennis O' Driscoll's 'Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney' is a very interesting, useful, attractive and comprehensive book (but 'comprehensive' is subject to {restriction}.) The opinion quoted on the front cover by Terence Brown in 'The Irish Times' isn't excessive: 'Richly enjoyable, consistently engaging.' The book can be strongly (but not unreservedly) recommended. It includes same fine examples of word-painting, such as this:

In answer to the question, What were your most memorable journeys? [After some routine and unimpressive mentions of 'a pilgrimage to Lourdes and 'a trip to my first rugby game'] the mention of 'the overnight sleeper from St Petersburg to Moscow, watching pine forests hurl past and the moonlit lines reel away and away from the back window of the last carriage.'

'Stepping Stones' is interesting and often enjoyable background information, not an aid to criticism. The biographical information it contains is put into perspective by Dennis O' Driscoll's review 'Homing Pigeon,' a review of Miroslav Holub's 'Supposed to Fly.' The review begins,

'Nobody who is familiar with Miroslav Holub's original and experimental output would expect him to publish an orthodox autobiography. Indeed, nobody who is aware of Holub's lifelong determination to produce hard-centred rather than self-centred work would expect an autobiography from him in the first place. Steeped since childhood in the ancient classics, he relished the fact that Homer, the greatest of all poets, casts "no biographical shadow" and never acquired 'a marketable "personality". (Published in 'Poetry Review,' Volume 80 No. 3.) If Seamus Heaney doesn't have something like a marketable personality, it isn't for want of trying, even if the marketing is of a superior kind.

Dennis O' Driscoll is indulgent towards Seamus Heaney as pontificator, the self-appointed Pontifex Maximus of contemporary poetry. 'Writers, according to Seamus Heaney, 'live precisely at the intersection of the public and the private.' (From Seamus Heaney's 'Foreword,' in Lifelines, ed. Niall MacMonagle.) Blake, Baudelaire, Trakl, Heym, Rilke, Kafka, Dostoevsky and many - or most - other writers wouldn't have regarded themselves as living at this intersection, whether precisely or otherwise. The true home of most true writers but not all is on the fringes of society. If poets are 'the unacknowledged legislators of mankind,' the stress has to be upon the unacknowledged. Holders of the post of Poet Laureate, such as Thomas Shadwell, Colley Cibber, Henry James Pye and Robert Southey (the best known of these) and Nobel-prizewinners such as Selma Ottiliana Lovisa Lagerlöf, Erik Axel Karlfeldt, Ivan Alexeievich Bunin, Frans Eemil Sillanpää and Seamus Heaney (the best known of these) aren't typical writers.

A degree of philosophical sophistication is irrelevant for poets, in general, but not for poets who are also commentators or critics, or, of course, literary theorists. A degree of philosophical sophistication puts so much of what's mistakenly described as 'literary theory' in a very unflattering light. The philosopher John R. Searle, for example, in his essay 'Literary Theory and its Discontents' (originally published in 'New Literary History' but republished in 'Theory's Empire: An Anthology of Dissent,' edited by Daphne Patai and Will H. Corral') gives an extended criticism of Derrida's misunderstanding of precision and vagueness, but the criticism applies too to Seamus Heaney's un-selfconscious misuse of 'precisely' here, 'at the intersection of the public and the private.' The literature concerned with precision and vagueness is very large. Bertrand Russell's essay 'Vagueness,' originally published in 'The Australian Journal of Psychology and Philosophy' was seminal. Mark Colyan discusses its metaphysical and linguistic aspects in Russell on Metaphysical Vagueness. In my page 'Interpretations,' I make a few remarks on the most celebrated instance in science of {restriction} applied to (precision), The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle.

Guinn Batten is one of the two contributors to 'The Cambridge Companion' writing from The Land of the Lethal Injection, otherwise known as the USA. (The other is Rand Brandes.) Guinn Batten is currently based in Missouri - the state's execution facilities are located at the infamous Potosi Correctional Center. Rand Brandes is currently based in North Carolina. The state's degrading execution facilities are located at Raleigh.

The page 'Gender and Sexuality Studies' of the site of Washington University in St Louis, Department of English, gives the information that Guinn Batten's academic interests include 'Women and Gender Studies.

In Guinn Batten's essay 'Heaney's Wordsworth and the Poetics of Displacement' as in Fran Brearton's feminist essay irresponsible suppositions multiply unchecked, unchecked, that is, by any responsible notions of evidence or plausibility. These academics seem to assume readers with almost unlimited credulity.

In connection with an episode in the 1799 Prelude of Wordsworth (lines 314 - 320 from the First Part) she writes, 'A woman wandering across the landscape bears a pitcher that suggestively evokes ...' I give her answer not immediately but at the end of this short section which discusses her essay. In the meantime, readers who aren't familiar with the essay can ponder, if they like, their own interpretation of 'pitcher' and later decide whether Guinn Batten is interpreting responsibly or irresponsibly. Wordsworth wrote:

And reascending

the bare slope I saw

A naked pool that lay beneath the hills,

The beacon on the summit, and more near

A girl who bore a pitcher on her head

And seemed with difficult steps to force her way

Against the blowing wind. It was in truth

An ordinary sight ...

It was an ordinary sight for Wordsworth but not ordinary for Guinn Batten.

It's surely irresponsible interpretation if an object can mean whatever the reader thinks might be plausible, including the academic reader with 'expertise' in Wordsworth studies. Is the pitcher a symbol here, or does the more straightforward interpretation make more sense? Perhaps the pitcher is simply 'a large jug, usually rounded with a narrow neck and often of earthenware, used mainly for holding water.' (Collins English Dictionary.)

She gives an imaginative interpretation of the jam jar in which the chestnut was planted ('Clearances 8,' 'The Haw Lantern'). It's mentioned in the lines 'my coeval / Chestnut from a jam jar in a hole.' Guinn Batten is very clear on this point. The jam jar is ' ... of course, an image of ... ' Again, readers not familiar with Guinn Batten's interpretation can interpret the jam jar themselves if they like, decide if there is an obvious image at all, and if there is, decide what they think is the image and compare it with the image so obvious to Guinn Batten. Again, her interpretation is given at the end of this section on the essay.

Earlier, she interprets digging and ploughing. The world of basic, necessary work - digging turf to heat water to boil potatoes, ploughing as a preliminary to sowing seeds - seems to mean nothing to this writer. It's simply the starting point for speculation (speculation offered as if it amounted to certainty.) 'Yet here, in that second or 'emptying' stage of disempowerment, a paradox emerges: in assuming the place of Mother Ireland, in displacing into his own voice her latent power, the Irish male poet, Coughlan contends, who elsewhere is '(phallically) digging and ploughing like his ancestors', ironically thereby 'becomes the culturally female voice of the subjugated Irish, about to inundate the "masculine" hardness of the planters' boundaries with "feminine" vowel-floods'.

She writes that Wordsworth 'is removed to Hawkshead Grammar School where (on a peninsula shaped, significantly, like ears) he observes a search party 'sounding' and probing with their 'long poles' to recover a dead body from the lake's depths.' The peninsula came to be shaped like ears for good geographical reasons.

The significance claimed for the shape of the peninsula is a reminder of the significance claimed for the shape of plants under the 'Doctrine of Signatures,' which effectively began in the first half of the seventeenth century, for example in the writings of Jacob Boehme. According to this doctrine, God had marked created things with a sign. Many herbalists believed that the appearance of a plant determined its medical uses. For example, the seeds of Skullcap, which was used for headaches, look like small skulls. The spotted leaves of Lungwort (used, completely ineffectively, for tuberculosis, look like the lungs of a patient with the disease, with the exercise of imagination and determination. Plants with a red signature were used for diseases of the blood.

Guinn Batten continues, in connection with the search party, 'They restore, one might surmise, in ghastly and masculine form, the maternal body that is now palpably absent for the young boy.

The lines which describe the supposed restoration of the 'maternal body' are lines 455 - 481 ('The Prelude,' 1805 version.) These are the significant lines:

... I

chanced to cross

One of those open fields, which, shaped like ears,

Make green peninsulas on Esthwaite's Lake.

[Wordsworth saw a 'heap of garments.']

... The

succeeding day -

Those unclaimed garments telling a plain tale -

Went there a company, and in their boat

Sounded with grappling-irons and long poles:

At length the dead man, 'mid that beauteous scene

Of trees and hills and water, bolt upright

Rose with his ghastly face, a spectre shape -

Of terror even ...

By transposing the sex (or 'gender') of the victim and ignoring completely his 'ghastly face,' then the maternal body becomes plausible, to Guinn Batten although not to me. If the search party had recovered a dead sheep from the lake which looked faintly bewildered, then the sex (or 'gender') wouldn't need transposing, assuming this was a female sheep, not a ram, but with a transposition of species this time, and ignoring completely its appearance, the maternal body could easily be restored, 'one might surmise.' Transposition enormously increases the commentator's freedom to interpret, to interpret arbitrarily, to interpret irresponsibly - to interpret badly.

Earlier in the essay, she has written about the associations of muddy ground and a thorn tree with 'maternal power.' She claims that Seamus Heaney 'echoes the two sources of mysterious power in [Wordsworth's poem] 'The Thorn' - the muddy ground and the upright thorn tree, both of which are associated with maternal power.' She claims that Seamus Heaney combines the maternal muddy ground and the maternal upright tree - to form what? She writes, 'he may even collapse them into a single image in the figure of the pump.' A few pages earlier, Wordsworth's gnarled thorn tree 'is arguably an allegory for the withering of liberty.' (The thorn before it became gnarled is a very unlikely allegory for liberty before it withered - the spikes don't convey liberty in the least.)

She offers yet another interpretation of this remarkable thorn tree: the thorn tree linked with destructive powers. Even though in Wordsworth's poem it seems much too small and much too old to be destructive in the least: 'Not higher than a two years' child / It stands erect this aged thorn;' she finds not the least difficulty in a decrepit thorn tree leading Irishmen to destruction. She writes, 'For an Irish reader such as Heaney that thorn's decrepitude - 'It looks so old and grey' - might find associative links with the maternal figure for Ireland, mentioned by Heaney in 'Feeling into Words', who in her destructive aspect leads her sons to martyrdom.'

These

interpretations can be presented very clearly using

Linkage

Schemata. In my notation, the angle brackets < > indicate

linkage, the square brackets indicate the things which are linked. So, the

first example below is read, 'muddy ground is linked with maternal power.'

![]() is used for the conjunctive 'and.'

is used for the conjunctive 'and.'

[muddy ground] < > [maternal power]

[thorn tree] < > [ maternal power]

[thorn tree (before gnarling)] < > [liberty]

[thorn tree (when decrepit)] < > [maternal, destructive Ireland]

[muddy

ground

![]() thorn tree] < > [pump]

thorn tree] < > [pump]

The poem by Wordsworth which gave rise to all this in the mind of Guinn Batten is a piece of near doggerel which has been ridiculed for its 'measurements,' but this wouldn't deter Guinn Batten in the least, if she ever decided to interpret the measurements as representing something on a much higher plane than the sphere of plausibility.

Not five yards from the

mountain-path,

This thorn you on your left espy;

And to the left, three yards beyond,

You see a little muddy pond

Of water, never dry;

I've measured it from side to side:

'Tis three feet long, and two feet wide.

The character of the narrator should be taken into account. In a note, Wordsworth writes, 'Such men having little to do become credulous and talkative from indolence; and from the same cause, and other predisposing causes by which it is probable that such men may have been affected, they are prone to superstition. On which account it appeared to me proper to select a character like this to exhibit some of the general laws by which superstition acts upon the mind.' The word 'credulous' here is worth noting ...

Guinn Batten likes using italics, as if to give the illusion that this is a writer aware of the exact weight and significance of each word in the creation of a meticulous argument, as here:

'Heaney, keenly reading an English and Romantic patrimony in which the poet imaginatively sounds in order to express a maternal absence linked to place, has developed a politics and poetics of embodiment inseparable from his politics and poetics of displacement. Further, he situates the experience of embodiment as displacement within Ireland's particular history of dispossession, which includes famine (the land's failure to fulfil, maternally, the human need to 'incorporate' its bounty) ...'

Here, I'd italicize a word she doesn't italicize, 'particular,' in the phrase 'particular history' to show the falseness of her interpretation. There was nothing particular about Irish famine, which was, supposedly, 'the land's failure to fulfil, maternally, the human need to 'incorporate' its bounty) ...'

Extracts from my section Agriculture, industry and famine on the page 'Feminism:'

'On the back cover of [Peter Mathias's 'The First Industrial Nation']: 'The fate of the overwhelming mass of the population in any pre-industrial society is to pass their lives on the margins of subsistence. It was only in the eighteenth century that society in north-west Europe, particularly in England, began the break with all former traditions of economic life.'

'In the 'Prologue,' this is elaborated: 'The elemental truth must be stressed that the characteristic of any country before its industrial revolution and modernization is poverty. Life on the margin of subsistence is an inevitable condition for the masses of any nation ... The population as a whole, whether of medieval or seventeenth-century England, or nineteenth-century India, lives close to the tyranny of nature under the threat of harvest failure or disease ...

'Larry Zuckerman, 'The Potato:' 'Famine struck France thirteen times in the sixteenth century, eleven in the seventeenth, and sixteen in the eighteenth. And this tally is an estimate, perhaps incomplete, and includes general outbreaks only. It doesn't count local famines that ravaged one area or another almost yearly ...'

There was nothing particular about Irish famines, then. The fact that famines no longer occur in developed countries is due to the fact that they are developed, that they have increased agricultural productivity by mechanization, that they have increased productivity in general.

These considerations offer none of the deep, or rather shallow, significance of Guinn Batten's interpretations. Centuries ago, life was far more significant for most people than today. If their plans for the day were ruined by poor weather, then the poor weather could be interpreted as 'directed at them personally.' The development of meteorology took away this particular significance. If their cattle produced much less milk or their crops failed, then there were forces to explain it, so much more personal and significant than any humdrum scientific explanation. If a plant has a shape that suggests a part of the human body, then this is significant, not accidental. New Age thinking perpetuates this discredited mode, Guinn Batten's interpretations likewise.

The answers to the two questions posed earlier. The pitcher carried by the woman suggestively evokes, according to Guinn Batten, uterine life or urn burial, two contradictory interpretations. The jam jar, according to her, is an image of transformed purpose.

For Guinn Batten, the hunger striker Francis Hughes offers further opportunities for 'interpretation,' in this case in terms of 'the self that imitates, one might say, the destructive feminine aspect of the land). From my page on Seamus Heaney: ethical depth?

'In 1978, a ten year old girl called Lesley Gordon was decapitated when a bomb exploded under the car of William Gordon, a member of the Ulster Defence Regiment who was taking his children to primary school. He was killed too. His seven year old son was severely injured by the blast.

'The bomb was planted by Francis Hughes. The year before, he had taken part in an attack on a police vehicle in which one man was killed and another wounded. In 1978, Francis Hughes was captured, after a gun battle in which one soldier was killed and another severely wounded. After his capture, his fingerprints were found on a car used during the killing of a 77 year old Protestant woman.'

She can offer an interpretation of his self-starvation in terms of 'the destructive feminine aspect of the land.' What interpretation would she offer of the decapitation of Lesley Gordon and the deaths and injuries he inflicted on the other people? In such a case as this, Guinn Batten's project is morally as well as intellectually indefensible.

A wider survey of Patrick Crotty's work than the comments on his contribution to the Cambridge Companion to Seamus Heaney would give a far more favourable impression. For example, the only clumsy thing in his essay, 'All I Believe That Happened There was Revision: Selected Poems 1965 - 1975 and New Selected Poems 1966 - 1987' is the title, which is explained by the first sentence of the essay. The title comes from 'All I believe that happened there was vision' is the last line of 'New Selected Poems 1966 - 1987,' from the poem 'The Disappearing Vision.' In this essay he writes not just well, and with insight, but sometimes wonderfully well and with wonderful insight, never more so than in his comments on the dropping of a poem from the revised Selected Poems. (I omit the previous five lines in the quotation here):

'What this reader cannot assent to is the absence of Station Island's poem on Thomas Hardy, an exquisite map of a stretch of the border between art and life distinguished by the most adroitly pitched adjective of the career (in the closing line of the first section):

And high trees round the house, breathed upon

day and night by winds as slow as a cart

coming late from market, or

the stir

a fiddle could make in his reluctant heart.'

And this is Patrick Crotty writing about the volume 'North:'

'The impersonal, sacramental idiom of the book must be counted one of the more notable stylistic innovations of late twentieth century poetry (its capacity to make grouped nouns glitter like sacred artefacts is extraordinary - " ... antler combs, bone pins, / coins, weights, scale pants").

'And yet North remains in the last analysis a tour-de-force, impressive certainly, but self-conscious and over-insistent where Wintering Out had been epiphanic.' (But I'd dispute the claim that the 'impersonal, sacramental idiom' amounted to an innovation.)

His Cambridge Companion essay doesn't have the distinction of this piece. He was writing now well below his best, like quite a number of the other contributors.

Many parts of Patrick Crotty's essay, 'The Context of Heaney's Reception,' have something of the staleness of a stale sandwich, with the difference that whereas the sandwich will still retain most of its nourishment, these have very little.

His style could be described as pedestrian or soporific or lethargic or stultifying, or all of these. An example: 'Corcoran is ... ready to temper approbation with approval.'

Style is only one factor and often not one of the important ones. Excellent scholars and commentators often have a style which is no more than adequate, or less than adequate. The style of some of the greater artists may be less accomplished than the style of some of the lesser ones. But Patrick Crotty's style has a linkage with the quality of his critical thought in this essay: both routine. Has he ever read George Orwell's essay, 'Politics and the English Language?' It contains this, ' ... it should ... be possible to laugh the not un-formation out of existence' and the footnote, 'One can cure oneself of the not un- formation by memorizing this sentence: A not unblack dog was chasing a not unsmall rabbit across a not ungreen field.' On the first page of his essay, 'While not inconsiderable, the varieties of official recognition granted to Frost ... and Hughes ...'

George Orwell would also have criticized Patrick Crotty's claim that 'Heaney's ability to evoke an action or sensation in a phrase constructed out of some of the most commonly used lexical resources is a very rare phenomenon in literature.' Instead of 'the most commonly used lexical resources,' why not 'the most commonly used words?' The claim also happens to be untrue. It isn't a 'very rare phenomenon in literature' and Heaney's language isn't consistently plain. The final line of 'A New Song' is only one example among many: 'A vocable, as rath and bullaun.'

Even so, there are depths below depths below depths (using 'depth' without any implication of profundity.) Patrick Crotty's essay is well written and full of good sense if compared with product such as Eugen O' Brien's 'Creating Irelands of the Mind.' I give an extract in my analysis of The Toome Road.

Patrick Crotty's style in the essay is generally poor in the old-fashioned way and rarely seems a product of the Postmodern Essay Generator, http://www.elsewhere.org/pomo/ which offers a convenient, automated way of avoiding thought, although he doesn't lack all talent for the style it generates, far from it. He describes Henry Hart's Seamus Heaney: Poet of Contrary Progressions as 'hermeneutically somewhat overcharged. The book's interpretation of the career trajectory as a matter of deepening mysticism and of a post-colonially driven, deconstructive response to the binarisms of the imperial English canon imputes a more systematic (and metaphysical) character to the corpus than that diverse and exploratory body of lyrics can easily bear, though the approach has the virtue of facilitating some interesting individual readings.' (Compare 'trajectory' here with Eugene O' Neill's 'parabola.' These geometrical analogies are quite popular with those who practise the exacting disciplines of Advanced Analysis of the Text.)

This could be interpreted as not a use of the style or an endorsement of the style, except that there's enough of his own comment in the same style mixed with what could conceivably be interpreted as criticism. His misuse of 'metaphysical' isn't an isolated example. A few pages earlier, he misuses 'epistemological:' some poems 'conduct a critique of the temptation towards a poetics of substance, revealing the poet's shrewd awareness of the problematic epistemological foundations of some of the most bravura effects of lyric art, both his own and others'. He doesn't, though, use or misuse 'ontological,' which must have required a degree of self-control on his part. However, he's careless with some less technical words, such as 'mysticism' and 'inherited,' (in 'the sonnet and its inherited privileges,'). He can also claim to find Trend and Pattern in things that surely don't illustrate Trend or Pattern.So long as the claim sounds very impressive, who will notice or mind? So, in connection with the Orcadian poet Edwin Muir, 'One of the persistent themes of Heaney's first two books ... is connected to a staple concern of the Orcadian poet: the progression from a childhood world of immemorial custom to a chastened state of knowledge identified with modernity, sexuality and an awareness of time.' Modernity is far less prominent in both books, particularly the first, than we'd expect, given the dates of publication, sexuality appears in neither book to more than a negligible extent, and the awareness of time is given less emphasis than we'd expect, given much of the subject matter.

Compare my comment on Rand Brandes, another contributor to The Cambridge Companion: 'Confining attention only to 'Digging' and 'Personal Helicon,' Rand Brandes is wide of the mark when he claims that 'From the opening poem of the book, 'Digging', to the closing poem, 'Personal Helicon', the poems are driven by the tensions between childhood innocence and insecurities and the adult realities and reconciliations.' This is a product of the word-sphere. The claim sounds good and impressive, but 'Digging' doesn't depict childhood innocence or insecurities, or adult realities and reconciliations. 'Personal Helicon,' a strong poem, depicts childhood enthusiasms or passions rather than innocence. It does depict insecurities, but not in any way adult realities and reconciliations.'

Patrick Crotty finds 'Three monograph studies distinguished by their combination of depth, critical flair and textual responsiveness may be described as indispensable to the serious student of Heaney.' These are 'Seamus Heaney and the Language of Poetry,' by the editor of 'The Cambridge Companion' himself, Helen Vendler's 'Seamus Heaney' and Neil Corcoran's 'The Poetry of Seamus Heaney: A Critical Study.' I don't discuss the editor's book in my pages on the poetry of Seamus Heaney, but I refer often to Helen Vendler's book on my page The Poetry of Seamus Heaney: flawed success and Criticism of Seamus Heaney's 'The Grauballe Man' and other poems. I refer very often to Neil Corcoran's book on the second of these pages. The case I present against them is vastly more detailed than the case in favour presented by Patrick Crotty. He's more impressed by Neil Corcoran than Helen Vendler. Helen Vendler's 'eclectic modus operandi,' like 'O' Donoghue's focus on questions of language,' 'mean that neither of these writers offers a fully comprehensive critical account of the Heaney corpus.' He doesn't explain why an eclectic modus operandi works aga'a fully comprehensive account.' Is a selective modus operandi more likely to give a fully comprehensive account?

He has some criticism to make of Neil Corcoran, but the criticism is as slight as Helen Vendler's criticism of Seamus Heaney: 'Corcoran takes what might seem a rather predictably chronological approach to the work,' but 'the strong narrative line is inflected throughout by his interrogative intelligence.' For my own comments on his 'interrogative intelligence,' see, again, my page Criticism of Seamus Heaney's 'The Grauballe Man' and other poems. In general, Patrick Crotty writes, his study 'stands out from all others by virtue of its scope, scholarship, seamless transitions between text and context and sustained elegance of style.' Its scope is far from comprehensive - Neil Corcoran simply discusses some of the poems in the volumes published by the time he wrote the book - and its scholarship is rudimentary. Since the context is part of the text of the book, the phrase 'transitions between text and context' is meaningless. (He writes of some of the poems' 'uncommon alertness to the needs of those who encounter them, their unfussy incorporation of gloss in text and gives the opening lines of 'Funeral Rites' as an example. This claim of his is simply untrue. The poetry provides absolutely no evidence for it.) The context he supplies is often shockingly bad (see, for example, my discussion of the context he supplies for The Frontier of Writing). As for 'sustained elegance of style,' I'd agree that the style is more elegant than Patrick Crotty's own.

Some of the essays are passable or perhaps passable, including David Wheatley's 'Professing Poetry: Heaney as Critic' and Justin Quinn's 'Heaney and Eastern Europe.'

These two essays aren't concerned directly with Seamus Heaney's poetry. Although they have some relevance to it, I don't discuss them here. David Wheatley has written about the poetry on his 'blogspot' at: http://georgiasam.blogspot.com/2009/05/seamus-heaney-abc.html

This gives 'an ABC of Heaney,' or more exactly an A-Z. This is informal and light-hearted but it's obviously intended to make some interesting and even serious points. Like the Cambridge Companion ('mutatis mutandis,' of course), it's varied in quality, but the bad outweighs the good. He makes his own contribution to the flourishing industry of Seamus Heaney Hagiography: 'Remarkably among poetic gods, Heaney is someone whose natural element is mildness first and last, a mildness that is a form of power, not weakness, and one whose poetic dividend, to use a Heaney word, continues to overflow bountifully for us mere mortals as wall as the god himself.' Again, this stops short of giving Seamus Heaney the power of miraculous healing, but perhaps only just. It's obviously not intended to be sarcastic. If it's intended to be mildly ironic, it's not nearly ironic enough.

Heather O' Donoghue's 'Heaney, Beowulf and the Medieval Literature of the North' is scholarly and accomplished, as are some sections of the editor's 'Heaney's Classics and the Bucolic.' Some of the quotations in the Analogy of the Greek Donkey come from the editor. His knowledge of the classical background is undeniable. Just as undeniable are his stunted critical capacities. He claims for Seamus Heaney, 'As a poet of the modernist tradition ... ' Seamus Heaney has no more claim to being a modernist than a builder of traditional Irish cottages (with certain Old-Norse, Old-English and Graeco-Roman features) has to being a modernist architect. This is simple misuse of terms.

In this chapter he investigates aspects of the classical background to Seamus Heaney's work and in particular 'the use of pastoral in his writing, whatever term we choose to describe it: pastoral, anti-pastoral, bucolic, eclogue, Doric.' (The mention of 'Doric' here is puzzling, with no close linkage with the other terms, which have obvious inter-linkages.) He examines in some detail the 'explicit eclogues in Electric Light: there are three of them, bearing very different relations to the Virgilian originals, the Eclogues or Bucolics. He gives the na'me of one of them almost immediately, 'Virgil: Eclogue IX.' (Not a good title for a contemporary poem in a contemporary book of poetry.) After almost two pages of discussion, 'we should consider the other eclogues in the book. There are two of them, one of which like 'Virgil: Eclogue IX' acknowledges Virgil explicitly. 'Bann Valley Eclogue' (which occurs earlier in Electric Light) has as an epigraph the opening line of the most famous of Virgil's Eclogues, iv, 1: 'Sicelides Musae, paulo maiora canamus -', 'Sicilian Muses, now we sing of greater things for a while.' After mentioning that there are two more eclogues to consider, he only gives one of the two. Again, there are almost two pages of discussion before at long last he divulges the identity of the third: 'Turning to the last of Elertric Light's eclogues, 'Glanmore Eclogue' ... '

The translation which Bernard O' Donoghue gives of the opening of Eclogue iv 1 is poor. There's no word in the original which corresponds to 'now' and 'paulo,' which means 'a little' or 'somewhat' should be taken as qualifying 'maiora,' 'greater things' (or 'more elevated things') and not with temporal significance. A simple, literal translation: 'Sicilian Muses, let us celebrate somewhat greater things.'

I could give a very extended discussion of the editor's approach in this chapter, but I think it's essential to recognize that the readership of the Cambridge Companion will generally be interested in much more than the classical background. This readership is entitled to expect much more, such as an examination of the artistic success of these three poems and some of the other poems he discusses, and, in view of the fact that Bernard O' Donoghue mentions modernism, an examination of Heaney's relationship to modernism, or lack of relationship. What he does do is make superficially impressive but spurious claims or arguments, ones which belong only to the word-sphere, such as this, 'What I want to argue is that, while we would expect the bearing of classical tragedy on the modern era to be an unconsoling one, we might look to the bucolic poems for comfort. This is not the case in practice; it is increasingly characteristic of Heaney's use of the pastoral to show it to be as devastated by violence and pity as tragedy.' The three eclogues - bucolic, pastoral poems - in 'Electric Light,' belong to the later period, in which his 'increasing' use of pastoral to show it as devastated by 'violence and pity' would be expected. I think that any responsible reader who actually reads the poems instead of depending on Bernard O' Donoghue's distorted account will find that this simply isn't so.

Without discussing the matter further, I simply give now an extract from journalistic material: 'David Hockney: A Bigger Picture, Royal Academy of Arts, review.' It's by Alastair Sooke and was published in 'The Daily Telegraph.' Alastair Sooke has been heavily criticized for the superficiality of some of his commentaries but in this piece he offers insights into painting and its modern history here which at least reveal gaps in Bernard O' Donoghue's approach and are surely transferable to the poetry of Seamus Heaney ('mutatis mutandis,' as Bernard O' Donoghue might put it):

'I could happily have done without the watercolours recording midsummer in east Yorkshire in 2004, or the suite of smallish oil paintings from the following year.

'Perhaps it’s a generational thing, but I don’t understand paintings like these. Fresh, bright and perfectly delightful, they are much too polite and unthinkingly happy for my taste: if they offer a vision of arcadia, it is a mindless one. Moreover, they resemble the sorts of landscapes that we expect from amateur Sunday painters. Hockney is anything but that – yet whatever game he is playing here eludes me.

'The iPad drawings from 2011 are similarly irksome. Some people get excited because they were made using a piece of fashionable technology (a tablet computer with a touch screen). Yet the technique is surely immaterial – as Hockney says, an iPad is just another tool for an artist, like a brush.

'What’s important is how they look: competent, easy on the eye (like art for magazine covers), but flat as though drawn with felt-tip pen. Some of the earlier pictures in the sequence, featuring tumbledown brick walls and tree stumps, look like illustrations for horror fiction. The later ones, full of frothy blossom and unfurling buds, have a trite cheeriness. They would look wonderful on the walls of a hospital, but the prominence they are given here is baffling. They appear to ignore an entire century of modern art — a narrative, incidentally, with which Hockney is fully up to speed. Why would someone so clued up wilfully paint as though surrealism, colour-field abstraction, minimalism and all the rest hadn’t happened? These images are so passť they feel like a provocation. I don’t get it.

'The memorable pictures are those in which the prevailing note isn’t cheeriness, but something much stranger, more ferocious and intense. There is a room full of paintings of hawthorn blossom. It looks like a patisserie in which someone has run amok: thick slugs of primrose pigment representing blossom have been slathered on to the canvases like icing and whipped cream.

'May Blossom on the Roman Road is palpably odd. The trees and shrubs have strong, simple silhouettes, like ornamental topiary. Beneath an animated sky awash with swirling blue and mauve marks, like something out of late Van Gogh, they appear to creep and throb, as though imbued with extraterrestrial life. This large work, painted upon eight canvases, transforms a mundane annual occurrence into something spectacularly weird.

'Another series, Winter Timber and Totems, introduces a touch of foreboding and forlorn melancholy. We are in the woods. Using an extreme Fauvist palette, Hockney paints tree stumps and felled logs. The culmination of the sequence is the 15-canvas oil painting Winter Timber (2009). An imposing magenta stump dominates the foreground. Next to it, piles of orange logs stripped of their bark lie beside a road that leads off into the distance. The track is flanked by slender blue trees, some of which start to bend and curl into a disconcerting vortex as they approach the horizon. Thanks to the preternatural colours, the scene feels uncanny, suffused with the intensity of a vision. It doesn’t take long to read the stump and logs as reminders of mortality, or to understand that Hockney has transformed a humdrum wintry scene into a gateway to the afterlife. The motifs – a backdrop of bare trees and piles of logs – made me think of Paul Nash’s unsettling Landscape at Iden (1929), another mysterious painting fraught with psychological disturbance, though recast with the bold colour combinations and simplified shapes of late Matisse.'

I make use of what I call adverbial criticism. Analysts may inform us - or make the claim - that a poet is dealing with death, tragedy, political violence, nature, love or another subject, and provide background information, explanation, sometimes 'theory,' which may amount to disguised or obvious ideology. All this may be very useful or completely superfluous. I recognize the importance of background and I have a very high regard for scholarly detail. There are analysts who specialize in such things and never evaluate. But an exclusive focus on the subject leaves unanswered such questions as these: is the poet dealing with the subject superficially, profoundly, blandly, routinely, one-sidedly, defensibly one-sidedly, indefensibly one-sidedly, in general well or badly, successfully or unsuccessfully? There are no mechanical ways of arriving at an estimate of a poet's success in these adverbial criticisms. Knowledge of the context is sometimes very important, sometimes not very important or completely unimportant. Seamus Heaney's poems Wolfe Tone, The Toome Road, and From the Frontier of Writing are examples of poems where distorted interpretations of Irish history hinder understanding, I think - or so I claim in my discussions.

Denis Donoghue (impossible to confuse him with Bernard O' Donoghue) gives an interesting discussion of the different views of context and background in F W Bateson and F R Leavis. ('What is Interpretation?' in 'The Practice of Reading.') His discussion is relevant to the use of context and background in The Cambridge Companion and innumerable other works: works of solid scholarship which make no claim to critical analysis, genuinely critical works and pseudo-critical works.

Kenneth Burke's 'Kinds of Criticism' covers some of the main ground, more comprehensively and more systematically but with less interesting detail by far, less interesting as a whole by far. F W Bateson is practising what Kenneth Burke calls 'extrinsic criticism,' Genetic: 'Concern with the relation between the poem and its non-poetic or extra-poetic ground.' And Implicational, ' concerned with the possible extra-literary causes of the poem.' F R Leavis is practising 'intrinsic criticism,' not the first kind he discusses, 'Poetics,' which 'in the strictest sense (as with the Poetics of Aristotle) deals with the poem as a member of a class' or the second 'Reviewing,' 'the "news" about a book, but the third, Textual Analysis, ' ... running commentary; line-by-line exegesis.'

Both F W Bateson and F R Leavis offer differing interpretations of a passage from Marvell's 'A Dialogue Between the Soul and Body' and a passage from Pope's The Dunciad and support their interpretation with evidence from close reading.

'In January 1953, the English scholar-critic F. W. Bateson, editor of Essays in Criticism, published a manifesto in that journal ...

'Bateson's main argument was that contemporary critics, resourceful and ingenious as they were, were irresponsible in many of their interpretations ... [they] did not take into consideration the context of the literary work they offered to interpret. By "context" he meant "the framework of reference within which the work achieves meaning.

'Bateson's main attack was turned on Leavis ...To sustain this position, Bateson invokes what he calls the intellectual context and the social context. He speaks of four stages in the widening scene of meaning. The first is the plane of dictionary meanings, the second is the literary plane (the tradition or genre to which the poem belongs), the third is the large intellectual setting, and the fourth is the social context. At that point in one's reading, Bateson claims, we have the correct meaning ... In the end, Bateson proposes what he calls a balance of literary and sociological criticism.

'Within a few months, Leavis replied to Bateson's in his own journal, Scrutiny. It is clear that he resented Bateson's claim to possess, as Leavis allegedly didn't, the scholarship to enable a just reading of Marvell and Pope. Leavis maintained that the production of this scholarship, on Bateson's own showing, amounted to the intrusion of a vast deal of critical irrelevance on the poem. With all his show of learning, Bateson was incapable of reading the poem.

'[F W Bateson quoted a 'Pope - Warburton note' to support his case.] Did Leavis give no credence to the Pope - Warburton note that Bateson quoted? He claimed to have read it, but to have found in it "nothing essential that I hadn't already gathered from the text itself." How much, or how little, such a note helps toward a right reading, he argued, "must be determined finally by a study of the text." The note doesn't settle any dispute.

'Leavis's case against Bateson ... is that he cannot read a poem. He is disabled from doing so by his confidence in what he calls contextual criticism, as if that relieved him from the labor of reading the words on the page. What is this "complex of religious, political and economic factors that can be called the social context," Leavis asks; a complex such that it enables us to restore the poem to its original historical setting and find there, with the conviction of certainty, the right interpretation? It is an illusion, Leavis insists ... In truth, it merely gives Bateson license for not, in any serious sense, reading the poem. Leavis is not making a case for ignorance. Knowledge, he says, "is needed for the critic's work, but the most essential kind of knowledge can come only from an intelligent frequentation of the poetry - the poetry of the age in question, and the poetry of other ages."

'I have no doubt that Leavis had the better part of this dispute. He won on points, if not by a technical knockout. He convicted Bateson of being thoughtless in the presence of Marvell's poem and of Pope's ... I remain unconvinced ... by his claim that the poem is determinately there, as if it were an object like any other. One's personal living would not be enough in reading the passages from Stevens and Yeats that I have quoted. Information is required. Leavis would probably retort: so much the worse for poems if they need, for an adequate interpretation, extraneous or private lore. As for the poem's being there, Leavis maintains that it is there in a sense in which it is impossible for any produced context to be there.'

He also makes very acute comments on feminist and similar interpretations of Macbeth in 'The Practice of Reading,' the title essay of his book, 'The Practice of Reading.'

'Since the early 1980's' a consensus on Macbeth has emerged which I'll try to describe: it satisfies the interests of social science, apparently, or of biographical diagnosis rather than those of criticism. By that difference I mean that the commentaries issue not in analyses of the language of the play but in an invidious account of the ideology that the play allegedly sustains: for that purpose, a reading of the play in the detail of its language is thought to be a nuisance.

...

'These versions of the new reading are not of course identical: we would not expect them to be, coming as they do from exponents of feminism, psychoanalytic criticism, and Old and New Historicism ...

'It would be helpful if I could quote a few passages of close reading of Macbeth. Not surprisingly, I can't. Close reading is not what they do. Several reasons suggest themselves. The first is that these critics are queering one discipline - literary criticism - with the habits of another - social science or moral interrogation. Their metier is not verbal analysis but the deployment of themes, arguments, and morally charged conclusions; hence the only relation they maintain to the language of Macbeth is a remote one. A second consideration: these critics evidently think that Shakespeare's language is transparent to reality and that the reality it discloses can be represented without fuss in political, moral, and psychoanalytic terms ... They take language for granted as providing direct access to reality and fantasy. Acting on this assumption, they also take for granted what Geoffrey Hill has called, with rebuking intent, the "concurrence of language with one's expectations." These critics have no sense of the recalcitrance of language, specifically of Shakespeare's English: they think that in reading his words they are engaging with forces and properties indistinguishable from their own ...

'It follows that when such critics quote, they do so merely to illustrate a theme, a discursive claim, or a diagnosis they have already produced ...'

These comments on interpretations of Macbeth are applicable to the interpretations of Guinn Batten and Fran Brearton in the Cambridge Companion.

Stephen Burt's review of 'The Cambridge Companion to Seamus Heaney' appeared in the London Review of Books, Volume 31 Number 11. He reviewed two books about Seamus Heaney in this issue: The Cambridge Companion and 'Stepping Stones: interviews with Seamus Heaney.' Both books are listed underneath the title, 'A Bit Like Gulliver,' with equal prominence, except that 'Stepping Stones' is listed first.

Stephen Burt's review of The Cambridge Companion is very surprising. It's very commendable that the London Review of Books gives their reviewers so much space - the reviews of the two books are on three pages - but Stephen Burt gives hardly any space to the Cambridge Companion. This is all he has to say about it in his review:

'Critics distinguish genres of poems about rural places - 'pastoral, anti-pastoral, bucolic, eclogue, Doric', as Bernard O' Donoghue writes in the Cambridge Companion to Seamus Heaney - and Heaney uses them all ... [There's nothing further about The Cambridge Companion after this brief mention.]

'The original bog poems, with their choppy stanzas, indicted what Justin Quinn, in the Cambridge Companion, calls Heaney's censurable complicity' (it is, Quinn adds, one of his 'central themes').

'The Companion concludes with John Wilson Foster's admiring overview of Heaney's poems since 1989: Foster envisions him as 'diplomat or ambassador', with his pan-European interests, his poems about jet planes, prefigured by 'Terminus' from The Haw Lantern.'

Although so much of my review here is critical, I've at least given the writers sustained attention and written about their work in detail.

Fran Brearton: Bowdlerizing and Breartonizing

Before I discuss Bowdlerizing in the Cambridge Companion, some supplementary material which mentions Fran Brearton and discusses some common faults in academic discussion of poetry - all the commentators in the Cambridge Companion are academic commentators. The material comes from the section on Seamus Heaney's poem In Memoriam Francis Ledwidge on my page Criticism of Seamus Heaney's 'The Grauballe Man' and other poems. I point out that Seamus Heaney made a bad mistake of fact and that amongst the commentators who failed to detect the mistake was Fran Brearton. An extract from the section after two images which illustrate the mistake:

Plaque at the Ledwidge Cottage Museum, Slane, Irish Republic.

Acknowledgments: Open Heritage.

www.openplaques.org/plaques/9824

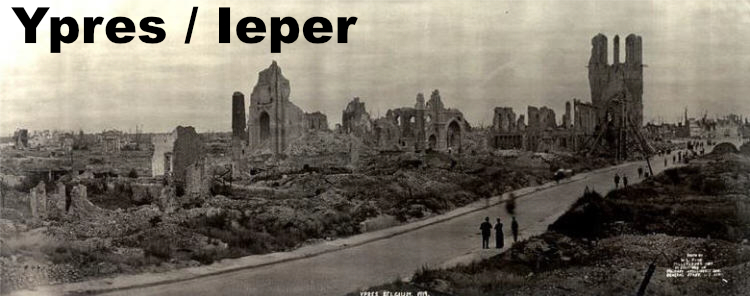

A photograph of some of the devastation in Ypres taken in 1919

'Seamus Heaney may have seen the plaque at the Ledwidge Cottage Museum in Slane, the Irish Republic. The poem mentions ' ... the leafy road from Slane.' It may have been the source of his mistaken view that Francis Ledwidge was killed in France. The title 'In Memoriam Francis Ledwidge' is followed by 'Killed in France 31 July 1917.' Whether the plaque was the source of his mistake or not, it wasn't an easy mistake to make. It was an inexcusable mistake.

'Francis Ledwidge was killed not in France but in West Flanders, Belgium. As the Website of the Ledwidge Cottage Museum correctly states, he was killed during the Third Battle of Ypres - by a shell near the village of Boezinge, North West of Ypres. Ypres is mentioned in the poem: ' ... a big strafe puts the candles out in Ypres.' Did Seamus Heaney believe that Ypres is in France? Ypres is the French name but the town isn't Francophone but Flemish-speaking and the Flemish name of the town is 'Ieper.'

'There were two previous battles of Ypres. The concluding phase of the third battle is commonly referred to as 'Passchendaele,' a name which, like the Somme, is one of the most evocative in the history of twentieth century war. The placing of these battle is a central fact, not a matter of minor importance. The devastation of Ypres and the devastating battles which raged around Ypres deserve scrupulous remembrance, not casual remembrance. The death of Francis Ledwidge deserves scrupulous remembrance, not casual remembrance.

'Not one of the discussions of the poem which I've read has mentioned Seamus Heaney's inexcusable mistake. Commentators who have failed to detect it may well be calling upon a completely inadequate knowledge of the First World War and the very complex conflicting and competing and complementary views of historians about issues which are relevant to their commentary. Fran Brearton discusses the poem in her academic study 'The Great War in Irish Poetry from W B Yeats to Michael Longley.' She is one of the commentators who have failed to point out the error.

'The requirements even for academic commentators on poetry tend to be rather relaxed ones - if the specialism is Irish poetry, make sure that you write in the approved academic style and provide enough citations and footnotes and a long enough bibliography in works to do with Irish literature. If the subject concerns the intersection of two very different fields, Irish poetry and the history and historiography of the First World War, then again, the full academic apparatus need only be concerned with Irish poetry - adequate knowledge of the history of the First World War is apparently not a requirement. To a significant degree, academic work in poetry may involve thoroughness in one field and primitive standards in a field which is relevant to it. Hence the many, many commentators on poetry who are content with superficial knowledge of another field, such as the history of the Northern Irish Troubles.'

Fran Brearton contributed the essay, 'Heaney and the Feminine' to the Cambridge Companion but since the writing of this abysmal piece, she seems to have written less and less from a feminist viewpoint.

In 'Heaney and the feminine,' she interprets with great freedom, irresponsibly. From my analysis of The Toome Road ('Field Work'):

'The line 'O charioteers, above your dormant guns' is given this interpretation by Fran Brearton ... 'the British 'soldiers standing up in turrets' are, in a sense, emasculated - their 'guns' are 'dormant' ...' The fact that these British soldiers were not firing their guns all the time, that almost all the time their guns were 'dormant,' unused, is obvious. To go from the obvious fact that the guns were not being fired to emasculation 'in a sense' is ludicrous - and disturbing, given the large number of British soldiers killed during the Troubles. This is closer to sneering than responsible comment. There are many, many images of Allied soldiers standing up in turrets as their vehicles entered the villages, towns and cities they had liberated with such sacrifices at the close of the Second World War in Europe. They had 'dormant' guns. Had these soldiers been emasculated 'in a sense' too? She claims that in 'The Toome Road' there's 'a collision of versions of masculinity,' the soldiers representing one version of masculinity. When allied soldiers fought against Nazi soldiers (and went on to liberate Belsen and the other camps) was this too 'a collision of versions of masculinity?' Or was there much more to it than that?

'Compare her interpretation of the 'dormant' guns with her interpretation of the pen and the gun in 'Digging' ('Death and a Naturalist'): 'the implied association of pen, gun and penis.' Did Seamus Heaney actually imply this facile association? Was it in his mind as he wrote? Her method of interpretation allows her to find anything 'implied' which suits her thesis, in defiance often of the clear meaning of a text, common-sense, and sometimes human values.

'Compare with this Freud's facile interpretation of a miner's strike - the miners' unwillingness to use their pick-axes (their penises) to penetrate the earth, regarded as feminine. The strikes of miners have generally belonged to a world of almost unimaginable harshness, concerned with very different matters. For example, at a meeting before miners began strike action in Northumberland and Durham in 1842: 'They catalogued the grim conditions in the mines, the bad air and long hours, the unjust system of fines, the payment by measure where the measures were set by the masters. They told of young children in the mines, of pay reductions ...' Or an earlier meeting before strike action began in Northumberland and Durham, in which one of the demands was for 'the reduction of hours for boys down the pit to twelve per day.' (Anthony Burton, 'The Miners.')

'Fran Brearton perpetrates something similar. She admits that this is 'to take images out of context,' but she seems completely undeterred, when she writes that 'in his criticism and poetry we see the landscape penetrated by the (phallic) pump ... Digging deeper into the ground simulates the sexual act ...' Has she found these images in the criticism and poetry or has she imposed them? Were the images she finds explicitly there implicit or not even implicit?

She criticizes The Second Vatican Council's view on motherhood, 'children ... need the care of their mother at home' without the least attempt to make clear its relevance to the poetry of Seamus Heaney. She gives an extended discussion of a poem by Medbh McGuckian which is no more relevant. The only reason for including it would seem to be to make a sneering comment about 'privileged' male poets. She writes,

'In the short poem 'Smoke', from The Flower Master, Medbh McGuckian, describing 'That snake of orange motion to the hills', observes that:

They seem so sure what

they can do.

I am unable even

To contain myself, I run

Till the fawn smoke settles on the earth.

'The 'snake of orange motion' is an image of the 'whins on fire along the road'; more obliquely, it is also the (male) Orange Order on their annual 12 July parade out of Belfast, with their political certainties. The poem is also about writing poetry, and about poetic form and tradition. Perhaps it is not stretching a point too far to suggest that the 'They' who 'seem so sure', in contrast to the uncontained female poet who breaks the boundaries of the line-ends, are also the (privileged) male poetic voices by which McGuckian has always been surrounded - Heaney, Muldoon and Carson among them.' This 'perhaps it is not stretching a point too far ...' is irresponsible and characteristic.

Radical feminists tend to be so sure that they can speak for other women. She seems 'so sure' that she can speak for Medhb McGuckian. This is Medhb McGuckian, in an interview, speaking for herself: 'I'm for feminism as long as it doesn't destroy in woman what is the most precious to her, which is her ability to relate and soften and make a loving environment for others as well as herself ... Sometimes there is something in feminism that demands you to be almost masculine and that's what frightens me a bit about it, or to sort of repudiate reproduction ... I find feminism attractive in theory but in practice I think it ends up influenced by lesbians and very lonely and embittered and stressed and full of hatred.' (Quoted in Medbh McGuckian's 'The Flower Master as a Critique of Female Modernism' by Lesley Wheeler.) This is the kind of feminism which won't appeal in the least to Fran Brearton, I think.

As for her comment about 'privileged' male poets, I wonder if she regards herself as privileged or unprivileged? The feminist academic who complains of being unprivileged (or exploited or suffering from male repression) is a familiar figure. Academics in this country are exposed to the lunacy of Government targets, Government interference combined with Government neglect and in general they are grossly under-valued (I write as someone who isn't an academic and has never been an academic), but academics aren't generally regarded as unprivileged, even feminist academics - except, often, by themselves. Fran Brearton is Reader in English at Queens University, Belfast and assistant director of the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry.

Before I discuss Fran Brearton's use of simplification words, I need to discuss further the dangers of irresponsible interpretation. Irresponsible interpretation restricts the free life of the mind, it increases the pressure for censorship and self-censorship and is dangerous but it has also been deadly, the cause of suffering and death. I don't claim of course that the interpretations of Guinn Batten and Fran Brearton are deadly in this sense.

Guinn Batten's linkage

[muddy ground] < > [maternal power]

has a disturbing context.

The interpretations of these writers, the irresponsible and often reckless interpretations of other writers on Seamus Heaney, aren't self-validating. It isn't in the least clear that muddy ground has to represent maternal power. If soil or the earth are interpreted as referring to maternal power, then the interpretation is one among a number of interpretations. 'Maternal' comes easily to Guinn Batten, but paternal interpretation came just as easily to William Empson. In the first chapter of 'Seven Types of Ambiguity,' he wrote, Wordsworth frankly had no inspiration other than his use, when a boy, of the mountains as a totem or father-substitute ...'

A very different interpretation of soil has been deadly as well as dangerous, the Nazi interpretation of 'Blut und Boden,' which can be translated as 'Blood and Ground' or 'Blood and Soil.' The Oxford Duden German Dictionary gives 'ground, soil' as the translation of 'Boden.'

From Anna Bramwell's 'Blood and Soil: Richard Walter Darré and Hitler's 'Green Party:' What [Blood and Soil] implied most strongly to its supporters at this time was the link between those who held and farmed the land and whose generations of blood, sweat and tears had made the soil part of their being, and their being integral to the soil.'

From 'Auschwitz: 1270 to the Present,' by Robert Jan van Pelt and Debórah Dwork: 'Historians played a major role in forging a seamless unity between the immutable power of the past and the irresistible force of ideology. This combative history began with an appropriately mythic Golden Age, when the area occupied today by southern Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Germany, and Poland was settled by Germanic tribes. For the National Socialists, this millennium of Germanic settlement was a Nordic paradise of blood and soil in which a racially pure people lived in harmony with the land that Providence had given them. But then, as was inevitable, paradise was lost. Hun raids forced these Germanic peoples to withdraw to the west.' And later, 'From the moment he became a member of the movement, Darré wielded great influence on the formation of National Socialist agricultural policy, and in June 1930 he was appointed head of the party's Agricultural Organization. One of his allies was that other agriculturalist - the thirty-year old Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler. Darré's vision of a Nordic peasant state paralleled Himmler's, and he joined the SS to become Himmler's closest adviser on the rooting of a people, or Volk, in the earth; as they called it, blood and soil. in 1928 Darré joined forces with Georg Kenstler, who had recently launched a magazine called 'Blut und Boden' and which advocated colonization of the eastern borderlands. Later, the Germans began their murderous drive to the east, of course.

So this was the interpretation of the soil according to Darré, Himmler and the Nazis in general:

[ the soil ] < > [ the blood, sweat and tears of the Germans ]

[ the soil] < > [ the roots of the Volk ]

There are Nazi interpretations of the soil, near-Nazi interpretations and non-Nazi interpretations of the soil, interpretations which are reckless but not dangerous, except to the free life of the mind. For example, the interpretation of Rudolf Steiner, who preached anthroposophy and who believed in a hierarchy of angels and archangels. According to Rudolf Steiner, 'the earth was alive: the soil was like an eye or ear for the earth, it was 'an actual organ'. '

[ the soil ] < > [ an eye or ear for the earth, an actual organ ]

Darré had a firm belief that the soil was alive too, and so have many supporters of organic horticulture in other countries. Lady Eve Balfour wrote a book called 'The Living Soil' in which she calls soil 'a living organism.' It's essential to distinguish between very well-grounded views and interpretations.

The linkage between the soil and extreme right wing views has been explored in Philip Conford's 'The Origins of the Organic Movement.' He discusses, for example, Jorian Jenks, editor of the Soil Association journal Mother Earth from its founding until 1963, who was an active supporter of the British Union of Fascists. Other early supporters of the organic movement were members of a secret society known as the 'English Mistery,' whose objectives included fortifying 'Anglo-Saxon' culture against supposedly pernicious 'foreign' influences like Judaism.

Scientific knowledge has a far better claim to knowledge than any of the interpretations, whether, Nazi, near-Nazi, non-Nazi or feminist. According to scientific knowledge, soil is the top layer of the earth's land surface of the earth. It's made up of small rock particles, humus and water. There are living organisms in the soil, larger organisms such as earthworms and smaller ones, including microscopic bacteria and fungi, but the soil isn't a living entity in itself - that's an interpretation, like the soil as maternal power or the claims for the soil of National Socialism. A water pump as a device for raising water against gravitational force is unproblematic. Fran Brearton's interpretation of the pump as symbolizing the phallus or the navel of the earth is very problematic. Poets are entitled to use symbols, of course, and to go well beyond the sphere of science, but interpretation, like science, has to recognize {restriction}, which makes less plausible interpretations which, it can be argued, are arbitrary. Although common sense isn't straightforward or decisive, it has its claims. It makes some interpretations seem difficult to take seriously.

Interpretations of matriarchy and patriarchy, like interpretations of the ground, the soil, the earth, can't be tightly controlled by feminists. Wherever evidence and those much maligned things, facts, are thought to be unimportant, then speculative interpretations multiply unchecked. So, in the 1860's J. Bachofen interpreted the Bronze Age and the Iron Age in these terms: there was an idyllic Bronze Age matriarchy destroyed by the patriarchal Iron Age. His ideas are discussed in Anna Bramwell's 'Ecology in the 20th Century, A History.'

In his late book 'The Anti-christ,' which contains his most intransigent attacks on Christianity, as the title would suggest, Nietzsche has acute things to say about Christian interpretation, which used to flourish without restraint. It has interesting linkages with radical feminist interpretation.

Fran Brearton uses such simplification words as 'patriarchal' and 'phallocentric.' These are also sneer words and cliché words. By {diversification} words as well as phrases can be clichés. Using words like this is perhaps supposed to prove something and to establish a kind of superiority, without the need to answer objections. It would be just as easy to use another simplification / sneer / cliché word and describe her approach as 'phallophobic.' Perhaps by now Cambridge University Press are publishing works on social and economic history which make free use of simplification phrases such as 'capitalist exploiters.' The mention of 'phallocracy' or 'patriarchy' shouldn't have a man creeping away in abject guilt, acknowledging the power of superior insights. The words are used as vague smears.

George Orwell's essay 'Politics and the English Language' has never lost its relevance. A contemporary version of the essay could make use of a phrase such as this, from Fran Brearton's essay, 'As Judith Butler notes in her discussion of the dialectic of Same and Other, that dialectic is 'a false binary, the illusion of a symmetrical difference which consolidates the metaphysical economy of phallogocentrism, the economy of the same.' This does have some kind of overall meaning, but not so Judith Butler's phrase 'the metaphysical economy of phallogocentrism,' which misuses the philosophical term 'metaphysical' and gives it no obvious meaning at all. The word is there only for effect. (Compare Patrick Crotty's misuse of another philosophical term, 'ontology,' in his reference to 'the austere, tightly argued ontology of 'The Peninsula' ' in another essay in the 'Cambridge Companion,' 'The Context of Heaney's Reception.') I touch upon metaphysics and ontology in my Introduction to Theme Theory.