Introduction: ideology and isolationist history

I was based in Northern Ireland for two years, at the height of the Troubles. In that time, I only crossed the border and visited the Irish Republic once and the visit was very short. After I left Northern Ireland, I made extended visits to the Irish Republic but I haven't been a visitor for a very long time. This is a country I would never visit again, a country I find flawed and pathetic in so many ways but I found some of the landscape deeply impressive - I'll simply mention here Dough Lough, Ben Bulben, and travelling through County Leitrim.

From the information available to me, it has become a real problem country in many ways, including economically, despite its economic strengths. I take the view that the most serious problems are to do with its defective, deeply selfish stance in the international order, its dependency on other countries to defend it. In these respects, it has been a problem country for a very long time.

At least the country has freed itself to a remarkable extent from the grip of the Roman Catholic Church, which has been exposed as a major offender in the matter of hideous abuse, including hideous sexual abuse. As in the case of the Church of England, the abuse has been carried out by a small minority but unchecked for far too long, owing to the indifference and inaction of far too many people in the church.

My pages on the Irish poet Seamus Heaney often discuss aspects of Irish nationalism and his nationalist views. This is from the page Seamus Heaney: ethical depth?:

'In 1978, a bomb exploded under the car of William Gordon, a member of the Ulster Defence Regiment who was taking his children to primary school. He was killed instantly, as was his ten year old daughter, Lesley, who was decapitated. His seven year old son Richard was severely injured by the blast

.'The bomb was planted by Francis Hughes. The year before, he had taken part in an attack on a police vehicle in which one man was killed and another wounded. In 1978, Francis Hughes was captured, after a gun battle in which one soldier was killed and another severely wounded. After his capture, his fingerprints were found on a car used during the killing of a 77 year old Protestant woman.

'This is the man, then, who has been described as 'an absolute fanatic,' 'a ruthless killer' who undertook a hunger strike and was the second man to die after the better known Bobby Sands. Francis Hughes came from Bellaghy, County Londonderry (or 'Derry') where Seamus Heaney grew up. The other hunger strikers were violent men too.'

I criticize Seamus Heaney's view of the hunger strikers.

From

'I

In the most important conflict of the twentieth century, The Second World War, the response of Irish nationalism more often than not was abject, cause for shame. The response of Britain was magnificent.

The historical surveys of Nationalist apologists have been completely inadequate, failing to take into account such considerations as these.

Extreme Irish nationalism has sometimes involved itself in the affairs of the rest of the world but principally to benefit itself. It has made contact with the Nazis for help and to Libya for help. Tony Geraghty: 'By 1972 arms cargoes were flowing into Ireland from Libya ... In June 1972, the Libyan leader Colonel Gadaffi, proclaimed: 'We support the revolutionaries of Ireland. We have stood by them ... We have decided to move to the offensive, to fight Britain in her own home.' ('The Irish War.') But otherwise, Irish nationalism has had some of the characteristics of a closed society. Tony Geraghty writes of the Irish War's capacity over the last three centuries 'to defy external influences, except where these served as tools to further the conflict. In the twentieth century, three world wars - two hot, one cold - came and went. A Soviet empire was erected and demolished and, with it, a comprehensive belief system - the Marxists 'materialist conception of history' - purporting to explain all human endeavour. Popes, presiding over a declining of their own, invoked the Almighty in a search for an answer to the Irish Question, without success ... None of these stirring events came close to penetrating the closed minds of Irish separatism, Ourselves Alone.'

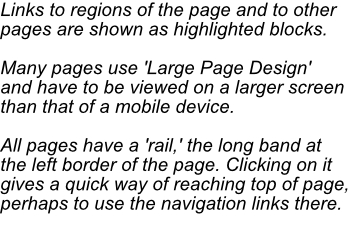

The Easter Rising of 1916 ignored the fact that Great Britain, amongst other war objectives, was fighting for the liberation of Belgium, almost all of it occupied by the Germans, and the liberation of the large area of France occupied by the Germans. The plight of other people was far from the minds of the rebels.

On my page on the death penalty, I include information on defence expenditure and the importance of defence expenditure, although without mentioning the Irish Republic. The Irish Republic is one of many freeloaders, one of the many countries which do hardly anything to defend themselves. They rely on other countries to maintain their security. However, none of the countries whose defence expenditure (as a percentage of GDP) is given has a defence expenditure as low as the Irish Republic's.

Military expenditure (% of GDP) in Ireland was reported at 0.2899 % in 2019, according to the World Bank collection of development indicators, compiled from officially recognized sources.

The police force and the armed forces are primary responsibilities of government: protection against internal threats and protection against external threats. The Irish republic has an effective police force but its defence forces are pitifully inadequate. It makes next to no attempt to contribute to collective security. Like so many European countries, its defence expenditure is a tiny proportion of GDP. It isn't a member of NATO. In a dangerous world, with threats from Russia and the deranged Iranian regime, which threatens the supply of oil to Ireland as well as Britain, it relies for its protection upon Britain, the United States and other countries which take seriously defence of the non-totalitarian world. My page on Israel and the Palestinians explains how Gaza and the Palestinian West Bank are protected by Israeli armed forces.

'On Ireland, finally, it is utterly impossible for me to speak with moderation, I loathe that romanticism.' Samuel Beckett, 'The Letters of Samuel Beckett Volume II, 1941 - 1956' (Cambridge University Press).

This page obviously isn't intended to be a contribution to scholarly history, which is the best of all correctives to those simplified, inadequate views of history which fall well below the standard of good popular history. The page was written to supplement my pages on Seamus Heaney. The Site Map gives access to my pages on the poet and his poetry. I admire very much the work of revisionist historians of Ireland and Northern Ireland, such as Ruth Dudley Edwards and R. F. Foster, the author of the superb 'Modern Ireland 1600 - 1972.' These historians, amongst other achievements, have transformed our understanding of Irish nationalism (the fact that in general they haven't transformed the understanding of Irish nationalist ideologists is no fault of theirs.) I'd suggest, though, that 'revisionist history' in connection with Ireland is a term which is badly in need of replacement. The term 'revisionist history' has now become tainted. There are 'revisionist historians' of the Holocaust who don't resemble in the least the revisionist historians of Ireland. The revisionist historians of the Holocaust are blatant ideologists who manipulate and distort historical evidence.

In this brief discussion, I work back in time.

Parnell came down the road, he said to a cheering man:

'Ireland shall

get her freedom and you still break stone.'

(Yeats, 'Parnell,' 'New

Poems.')

Ireland's freedom is a grand, inspiring, overwhelming, rebel-rousing and often rabble-rousing aspiration. Freedom from grinding toil, like freedom of thought, belongs to a much more disappointing sphere of reality, one which is much less important to mythologizers, but a myth can bring consolation to the downtrodden. Harsh lives can break free from their burdens, insignificant lives, can break free from their insignificance, given a powerful mythology. Mythologies can console but, more importantly, give hope, almost always spurious hope. The mythology must, however, be not just resonant but essentially simple.

There's vast contrast between Nazi mythology and Irish nationalist mythology. Nazi mythology has been incomparably more harmful than Irish nationalist mythology. All the same, there are some linkages, though recognition of these should never in any circumstances amount to equating Nazism and Irish nationalism.

The mythology of Irish nationalism and Nazism are essentially simple. Marxism and materialist interpretation offered a similar simplicity - the glorious triumph of the working class (the class into which I was born, incidentally, and which I resolutely defend, but with all kinds of qualifications.) The gross deprivation which motivated this ideology has been largely ended in capitalist countries by capitalist efficiency. There are still issues which motivate the remaining Marxists, but they lack the essential simplicity required for a full-blooded mythology. Not many Marxists and neo-Marxists believe that the dictatorship of the proletariat will eventually come about.

Every mythology is subject to {restriction}. There are blemishes, blots, faults and cracks. The mythology is less than blissful and less than satisfying. Often, there are external enemies, real or perceived. Fellow believers may be regarded as external enemies. They believe in a variant of the mythology. Nazism was monolithic and untroubled by heresy. Catholic Christianity, on the other hand, was racked by doctrinal disputes.

Nazism's chief enemy, according to Nazis, was a defining enemy, an enemy which played an essential role in the ideology: the Jews. The Jews were regarded as the flaw, the worm in the bud, which gave {restriction} to Nazi feelings of all-encompassing grandeur. My poem 'Heydrich' shows the extreme unease of the fanatical Nazi Heydrich and his determination to rid the Reich of people he regards as obstacles to the perfection of the Reich.

So, the unease of so many nationalists has known no respite. The most radical and ruthless way of dealing with the flaw, the obstacle, terrorist action to force the Protestants to change their minds and to force the British government to give way, has failed.

The more thoughtful nationalists will see that there is no way out of the dilemma. It's overwhelmingly unlikely that Ulster - present-day Ulster, not the historical Ulster - will become absorbed into an Irish republic. Even if this momentous political change were enforced, against the wishes of these Protestants, the united Ireland which resulted would be unstable. .

When there are two opposing sides, enemies to each other, then it's overwhelmingly likely that both sides will commit mistakes, sometimes hideous mistakes, and have flaws, sometimes hideous flaws. The attitude that one side is as bad as another is a common one, but is just that, an attitude. In the action-sphere, as opposed to the word-sphere or the attitude-sphere, it's generally impossible to satisfy both sides equally or to implement opposing plans of action. To satisfy one side may be to alienate the other, and the fact that the side which is satisfied has committed mistakes, sometimes hideous mistakes, and has flaws, sometimes hideous flaws, can't stand in the way of taking action. The necessity of taking concrete action which will benefit one side and disadvantage the other, despite any troubling complexities, is familiar from judicial decision- making. After the evidence and arguments have been presented, someone has to be awarded custody of a child, for example, even if the custodian is less than perfect.

I refuse absolutely to consider that the allied cause and the axis cause, the opposing causes during the Second World War, were 'both as bad as each other.' Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Dresden, such less commonly cited issues as segregation in the American armed forces, the fact that Stalinist Russia was part of the anti-axis coalition, for that matter, don't affect the fact that the allied cause deserved to win and the axis cause deserved to be defeated - there was no completely virtuous third force in waiting. The pseudo-argument of listing has become a common tactic. So, a list of some of the places bombed in the Second World War is intended to demonstrate the shocking inhumanity of both sides. Events vastly different in their motivation and their intended results are combined - Hiroshima, Nagasaki, Warsaw, Coventry, the London Blitz, Dresden ...

My own examination of the evidence and arguments leads me to the conclusion that in this same sphere of practical outcomes, the continuance of a divided Ireland, the disappointment of hopes for a united Ireland, is far better than the alternative or alternatives. The fact that the Shankill butchers and many other loyalist killers were working towards this outcome isn't a decisive objection in the least. The shooting of unarmed demonstrators by soldiers of the Parachute Regiment - the most serious breakdown in discipline in the British army during the Troubles - isn't to be equated with the killings of the Shankill butchers or the IRA. Only a completely inadequate ((survey)) of the range of killings and other violent acts during the Troubles could possibly give overwhelming significance to this event - except for the completely understandable sorrow and anger of the relatives of the unarmed people who were shot.

For a discussion of Seamus Heaney and the British army, Seamus

Heaney and republican punishment, Seamus Heaney and the hunger strikers

Seamus Heaney: ethical

depth?

The bleakness and harshness of the Troubles in Northern Ireland were compounded by the fact that the Troubles went on for a very long time, longer than The Thirty Years War, although vastly less devastating. There are still sporadic incidents, intensely painful for those caught up in them. But some Irish people succeeded in persuading others that the Troubles were almost uniquely bleak and harsh, that the British 'army of occupation' was the most horrific in history, that Irish sufferings over the centuries have been almost uniquely atrocious, that the English 'oppressors' were the worst there have ever been. Anyone who knows just a little about The Thirty Years War, The Spanish Civil War, The Second World War in the East (Stalingrad and other campaigns), The Second World War in the West, the war against Japan on the Pacific islands, the Second World War in all its areas, the First World War - the Somme, Passchendaele and the rest - realizes that with its just over three thousand dead, the Troubles were not the greatest calamity of the twentieth century or previous centuries. The bombing during the British Blitz, the bombing at Guernica, Rotterdam, Dresden, Hamburg and other places, was on a different scale. In the city where I live, Sheffield, over 600 people were killed in two nights of bombing. This is much higher than the total number of deaths in the peak year of the troubles for the whole of Northern Ireland, with three times the population. See:

http://wapedia.mobi/en/Sheffield_Blitz

But I still agree with this, from the review of 'Bloody Belfast' on the Daly History Blog: 'What this book by Ken Wharton tells us, is that we need to rethink what we think of as ‘war’, beyond the two world wars. Just because active service in Belfast and Londonderry and Crossmaglen did not meet our narrow definition of battle, it does not lessen the bravery of the men who served there. Those of us reading from the comfort of our armchairs cannot begin to imagine the human strain of being on service in the Province at the height of the Troubles. If anything Northern Ireland was a more difficult kind of war, as with yellow cards and rules of engagement, the Security Forces were incredibly hamstrung in what they could do.'

A crippling lack of historical knowledge underlies the attitude of those who think that during the Troubles, the British army acted without restraint. The opposite is true. Those who take up arms against a government have in the past generally been treated with the utmost ruthlessness. The British army during the Troubles was obviously benign by comparison with the armies which have executed not just armed insurgents but often their families and hostages with no connection with the insurgents. Anyone who denies this would do well to investigate such incidents as the Nazi reprisals at Oradour-sur-Glane and Tulle in France. At Oradour-sur-Glane, they killed 642 of the inhabitants of the village in reprisal for attacks by French maquisards. At Tulle, they hanged 99 men from lamp-posts and balconies, in reprisal for attacks. But in the war in the east, they far exceeded the atrocities which took place in Western Europe.

After the Partition of Ireland in 1921, ratified by the Irish parliament in January 1922, a major part of Ireland was no longer subject to British rule and free to determine its own affairs. The Irish Civil War (1922 - 23) was fought by two factions of the republican movement: the Provisional Government against the Irregulars. Eventually, the Irregulars used guerilla tactics. Armed insurgents were treated far more harshly than during the Troubles. The government imposed the death penalty for those found in possession of arms and executed 77 people for the offence. The orders for execution were signed by Kevin O' Higgins, who was assassinated by the IRA in 1927.

Yeats admired him and his poem 'Death' ('The Winding Stair and Other Poems') was inspired by him. See also Yeats' poem 'The Municipal Gallery Re-visited' ('New Poetry'):

Kevin

O' Higgins countenance that wears

A gentle questioning look that cannot hide

A soul incapable of remorse or rest;

The loss of life during the Civil War was much less than during the Troubles - 927 people by June 1923, including the 77 executed. The government of the Irish Free State wasn't especially ruthless by the norms of the time.

The reprisals carried out by the Germans during The Second World War put the restraint of British policy and British troops during the Troubles in context, for example two reprisals in June 1944 in France, the hanging of 99 men from balconies and lamp posts in Tulle and the massacre of men, women and children in Oradour-sur-Glane. They are described in Max Hastings' 'Das Reich.' Referring to the conduct of British troops during the Troubles in terms which would fit the conduct of the German SS at Tulle and Oradour-sur-Glane is nationalist distortion at its worst.

Henry McDonald's book 'Gunsmoke and Mirrors: How Sinn Féin Dressed up Defeat as Victory' is indispensable for understanding the Troubles. All the injuries and all the lives lost brought a united Ireland no nearer. He concludes that 'Americans at least [not all, of course] had seen through ... the polite fiction that he final outcome had been some sort of honourable draw.' It was the British state that had won.

The bombing of Britain during The Second World War makes it abundantly clear that a modern, technological state has the capacity to withstand catastrophic damage. Henry McDonald writes about the work of the academic Rogelio Alonso, who wrote 'IRA and Armed struggle.' He mentions 'the refreshing honesty of his interviewees, the majority of whom were IRA veterans. One of them, for example, admits to Alonso that 'There was never going to be a military victory. [The British government] is probably one of the most sophisticated fighting governments in the world, so to even think that you were going to face down and defeat a British government was lunacy.

'Another of Alonso's interviewees also muses on the notion of British stubbornness. This IRA volunteer is sceptical about the efficacy of bombs such as the one that devastated Bishopsgate in the City of London in 1993: 'You are not going to bring the financial institutions of capitalism to their knees with one bomb. Hitler couldn't in the Second World War.

Views like the ones above are peppered throughout Alonso's masterly study of the IRA's armed campaign and help debunk the myth of an 'undefeated army', let alone the achievement of some sort of victory.'

During the Troubles, as during the Second World War, Britain fought against a genuinely ruthless and morally depraved regime. Henry McDonald writes '... when Britain went to war over the Falklands in 1982, republicans of all hues backed the Argentine Junta, a vile dictatorship that like all tyrannies invaded the islands as a populist distraction form its crimes and human rights abuses at home. The British defeat of that Junta precipitated its fall and ultimately the restoration of democracy!' I discuss the fight of Britain against a far worse regime, Nazi Germany, in the next section, and the fact that many nationalists were indifferent to the fight or even supported Nazi Germany.

Or, instead of defending the Nazis, some nationalists made morally indefensible linkages. Henry McDonald writes, '... Danny Morrison, while Sinn Fein Publicity Director, drew parallels between the IRA and the Maquis or French Resistance of World War Two. Murals too made comparisons between the Nazi treatment of Jews, Gypsies and any political opponents, and the British treatment of nationalists and republicans in Northern Ireland.

'The double irony of the Nazi parallels is that present-day republicans still revere IRA leaders who were allied to Nazi Germany in the Second World War. They still gather every September to honour Sean Russell at a statue of the IRA commander during World War Two in Dublin's Fairview Park.' [Sean Russell was] 'an ally of the Nazis who died on a German submarine on route back to Ireland to foment a terror campaign aimed at undermining Britain's and the Allies' war effort.'

If his main criticism is reserved for the delusions of nationalists who supported bombs and bullets, and those who planted the bombs and fired the bullets, he's unsparing of the Protestant paramilitaries and their supporters. '... the loyalist paramilitary groups were inflicting almost daily acts of blatant sectarian butchery on vulnerable Catholics. Their so-called 'terrorise the terrorists' strategy was in reality the terrorisation of an entire community.'

There are many, many academic studies of the First World War and Second World War which are exemplary, outstanding, but the period of the Troubles is less well served, even taking into account the obvious fact that this was - or, pessimistically, is - a vastly smaller conflict. It's all the more important to take account of non-academic contributions to understanding of the Troubles. Many of these are incisive and exceptionally interesting. As so often, whilst many academics have pontificated, mythologized, ignored the most obvious evidence which would falsify their explanations, many journalists have written accounts which increase our understanding enormously.

Malachi O' Doherty's 'The Trouble With Guns: Republican Strategy and the Provisional IRA' is one such account. M L R Smith's review in the journal 'Studies in Conflict and Terrorism,' is headed 'The Trouble With Guns ... and Academics.' The review begins,

'Every phenomenon, according to a former colleague of mine, is surrounded by one big myth. I wonder if the big myth about academia is that it promotes original and creative thinking. Too often it seems academics, in the social sciences at least, behave like pack animals - chasing intellectual fads, in hoc [sic] to orthodoxies, acting as supporting counselors to the consensus - rather than challenging assumptions and revising the received wisdom that underpins conventional thinking. It is with pieces of outstanding historical revisionism like The Trouble With Guns that doubts about one's chosen profession arise. This book is the first to offer [the book was published in 1998] a serious reinterpretation of the Provisional IRA and Northern Ireland history since 1969. In a way, we have waited over twenty years for such a study tthat questions the popular imagery surrounding this small, but still controversial, and highly written about, civil conflict. Yet the disturbing truth for an academic profession that cherishes its freedom of inquiry is that a book of this nature should have been written long ago by one of their number. The fact that a journalist, Malachi O' Doherty, has accomplished this task is evidence not only of his intellectual rigor, but also of the academic neglect of the military and strategic dimensions of the conflict, the result of which has been to allow partial, ill-formed images to flourish unchallenged.'

Tony Geraghty's 'The Irish War: The Military History of a

Domestic Conflict,' also published in 1998. is another work by a journalist

which deserves careful study. Tony Geraghty was chief reporter for 'The

Sunday Times.' His book combines vivid reportage and acute analysis.

I lived in Northern Ireland during the

Troubles, when the Troubles were at their worst. For me, this was a happy

time but overshadowed by the atrocious events of the time. I was

sustained by a wonderful friendship. My visits to Belfast left

an indelible impression but I was based in one of the safest areas of

Northern Ireland. Even so, a few days before I left

the Province for England, I heard a massive explosion in Coleraine which killed six

pensioners and injured 44 people, including schoolchildren. I believe that the engine of the car bomb ended up in the barber's

where I had my hair cut a week or two before.

Above, the effects of the car bomb planted by the Provisional IRA in Coleraine, County Londonderry.

From the Wikipedia entry on the bombing:

'Several of the wounded were maimed and left crippled for life. The bomb left a deep crater in the road and the wine shop was engulfed in flames; it also caused considerable damage to vehicles and other buildings in the vicinity. Railway Road was a scene of carnage and devastation with the mangled wreckage of the Ford Cortina resting in the middle of the street, the bodies of the dead and injured lying in pools of blood amongst the fallen masonry and roof slates, and shards of glass from blown-out windows blanketing the ground. Rescue workers who arrived at the scene spoke of "utter confusion" with many people "wandering around in a state of severe shock". Five minutues later, the second bomb went off in the forecourt of Stuart's Garage in Hanover Place. Although this explosion caused no injuries, it added to the panic and confusion yielded by the first bomb.

...

'In the immediate aftermath of the blast, there had been several seconds of "deathly silence" before "all hell broke loose", with hysterical people rushing from the scene and others going to tend the wounded who were screaming in agony.'

See also my poem Sailing from Belfast, at the time of the Troubles.

There are startling gaps and omissions in the Irish nationalist view of history. The most important single omission is The Second World War - not, obviously, a minor one. According to the mythology of Irish nationalists, nobody has suffered like the Irish, nobody has exploited others like the English. But in a conflict which was more devastating than any other in history, which inflicted suffering on a greater scale than any other, the English, and the other countries of the United Kingdom, including Northern Ireland, a constituent part of the United Kingdom, carried on the war against Hitler alone, for a time, with exiled groups from many countries and volunteers from many countries, including volunteers from the Irish Republic, who served in large numbers. Irish nationalism and the Irish Free State stood aside and did nothing. The IRA actively sought help from the Germans. During The Second World War, the Irish Free State was neutral. After the death of Hitler, condolences were offered from only two sources, Portugal and the government of The Irish Republic. 'The Cruel Sea' is a popular novel by Nicholas Monsarrat.' The factual claims here are confirmed by Brian Girvin in his scholarly 'The Emergency: Neutral Ireland 1939 - 1945).

'...it was difficult to withhold one's contempt from a country such as Ireland, whose battle this was and whose chances of freedom and independence in the event of a German victory were nil. The fact that Ireland was standing aside from the conflict at this moment posed, from the naval angle, special problems which affected, sometimes mortally, all sailors engaged in the Atlantic, and earned their particular loathing.

'Irish neutrality, on which she placed a generous interpretation, permitted the Germans to maintain in Dublin an espionage-centre, a window into Britain, which operated throughout the war and did incalculable harm to the Allied cause. But from the naval point of view there was an even more deadly factor: this was the loss of the naval bases in southern and western Ireland, which had been available to the Royal Navy during the first world war but were now forbidden them. To compute how many men and how many ships this denial was costing, month after month, was hardly possible; but the total was substantial and tragic.

'From a narrow legal angle, Ireland was within her rights: she had opted for neutrality, and the rest of the story flowed from this decision. She was in fact at liberty to stand aside from the struggle, whatever harm this did to the Allied cause. But sailors, watching the ships go down and counting the number of their friends who might have been alive instead of dead, saw the thing in simpler terms. They saw Ireland safe under the British umbrella, fed by her convoys, and protected by her air force, her very neutrality guaranteed by the British armed forces: they saw no return for this protection save a condoned sabotage of the Allied war effort: and they were angry - permanently angry. As they sailed past this smug coastline, past people who did not give a damn how the war went as long as they could live on in their fairy-tale world, they had time to ponder a new aspect of indecency. In the list of people you were prepared to like when the war was over, the man who stood by and watched while you were getting your throat cut could not figure very high.'

Mark McShane's 'Neutral Shores: Ireland and the battle of the Atlantic' is an account by an Irish writer. It includes accounts of the warmth and helpfulness of ordinary Irish people. (A Second Mate recounts that 'The people of Courtmacsherry nearly killed us with kindness.')

Brian Girvin writes, 'Eire did remarkably little to ensure that Germany did not win the war. The government acted in public as if it did not care who won and hinted at times that there was no real difference between the two sides. Yet Germany was a continuing threat to Irish sovereignty. Hitler was contemptuous of neutrality in general and if the Nazis had won the war, the likelihood of any neutral state remaining independent seems very low indeed.'

The Irish historian Ryle Dwyer argues that Irish neutrality was generally implemented in a way favourable to the allied cause, in his book 'Behind the Green Curtain: Ireland's Phoney Neutrality during World War II.' His short piece in the Irish Examiner, So we should have sided with the allies in 1942? That's nonsense presents some of the arguments he uses in the book.

The practice, if not the policies, of the government of the Irish Republic may have been helpful to the Allied cause in some ways, but not nearly enough to overturn the conclusion that the government failed, and failed comprehensively. One of the many abject failures was the failure to honour the Irish people who had fought against Nazism. The post-war record, like the record of the war years, is cause for shame.

If Irish governments have failed to recognize the achievement of these people, there should be no general failure to recognize it. The Website of Kevin Myers, the Irish writer, includes an impressive page Address at St Patrick's Cathedral on Remembrance Sunday which pays tribute to the courage and sacrifices of the many individual Irish men and women who volunteered to fight against Nazism or who helped in the war effort. (He mentions the fact that 'In all, 16% of British military nursing deaths were of Irishwomen.)

There were exceptions, then, and very significant exceptions, to the Irish Republic's somnolence, described by F S L Lyons in these terms: 'The tensions – and the liberations – of war, the shared experience, the comradeship in suffering, the new thinking about the future, all these things had passed her by.'

There's an implicit claim in the poetry of Seamus Heaney, as in the nationalist ideology, to occupation of the moral high ground. Far too often, commentators on the poetry have accepted this claim. Like Vichy France, but not to nearly the same extent, nationalism showed moral failure in confronting the worst challenge of all. The challenge that many nationalists still prefer to address is completely different in scale and kind: the prejudices of Northern Irish unionism, prejudices which made it less likely for a Catholic to find a job, not the Nazi prejudices which resulted in mass murder.

Irish nationalists often show a gross failure of {adjustment}, a failure to take account of changed moral realities.

I think that Seamus Heaney mentions the Second World War only once in his poetry, in part 1 of 'To a Dutch potter in Ireland,' dedicated to Sonja Landweer, who was in the occupied Netherlands during the Second World War - and a section 'from the Dutch of J C Bloem.' (I discuss Seamus Heaney's translation in 'Seamus Heaney: translations and versions.') It was a mistake to use this Dutch poem as a starting point. The 'mention' of the war is a bare mention. The poem could have mentioned the terrors of everyday life in that place, at that time, the executions, the reprisals, and of course the deportations to the extermination camps. There's mention of only one aspect of the war, this:

Night after night instead,

in the Netherlands,

You watched the bombers kill ...

This is unnecessarily obscure. The allusion could and should have been expressed more plainly, 'the bombers' identified. For the Dutch, there was an absolute difference between the two, representing the difference between death and hopes of survival and hopes of liberation. The German bombers were the ones that bombed Rotterdam in May 1940, killing 800 people. The death toll would have been far higher but for the fact that much of the population had already fled the centre for safety. The British bombers were the ones which dropped food to the starving Dutch during 'Operation Manna' near the end of the war.

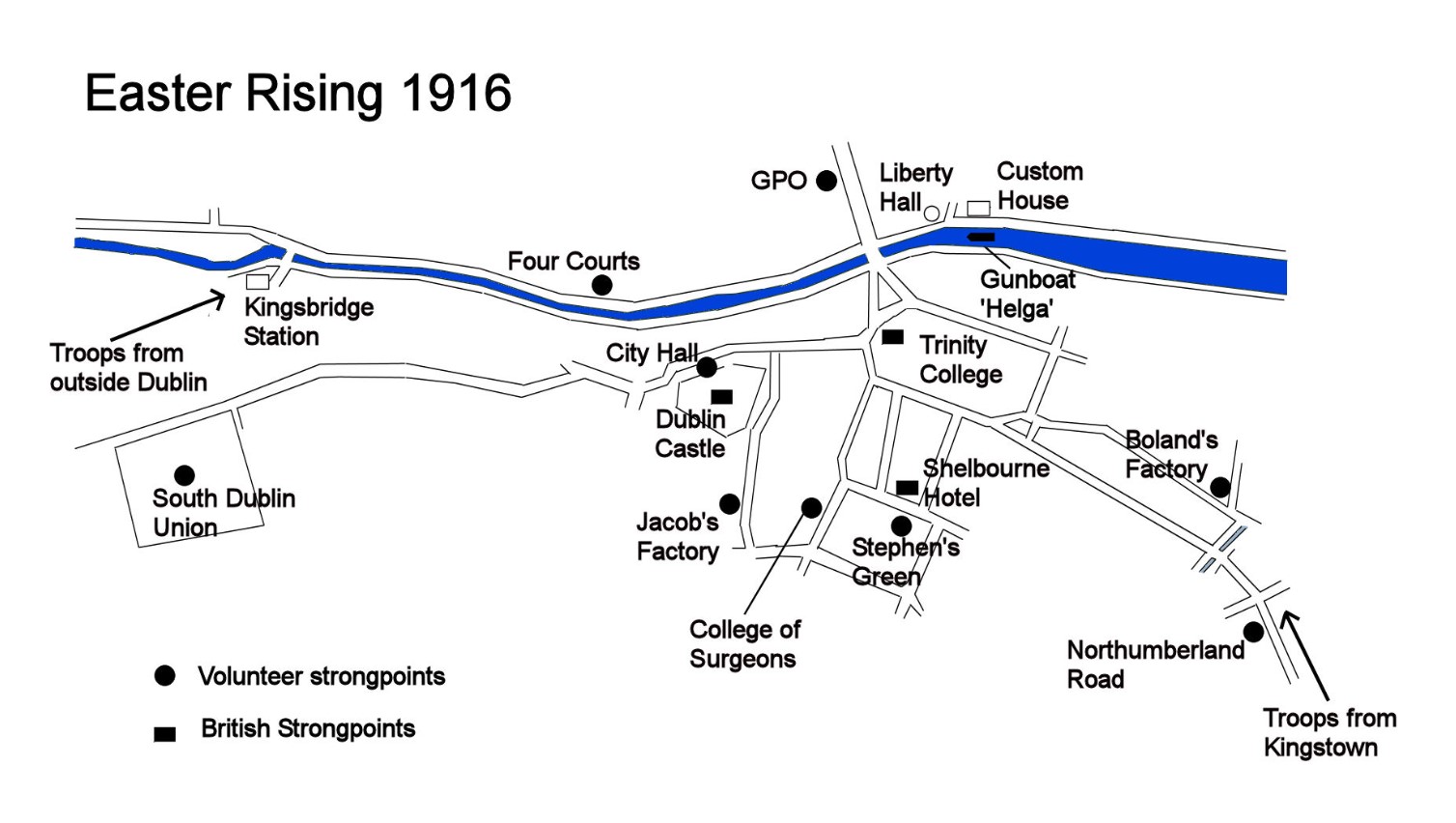

Above, Thomas Clarke, one of the leaders of the rising and executed by the British on 3 May, 1916.

My discussion of Seamus Heaney's poem In Memoriam Francis Ledwidge includes a discussion of Ireland during the First World War.

Although I think Seamus Heaney retained uncritically some of the nationalist distortions of history, this isn't an objection to his poetry. The chief responsibility of a poet isn't to give a scrupulous, comprehensive and well-argued survey of history. The 1916 uprising is instructive. In 'Outcasts from Eden,' Edward Picot has interesting comments:

'...like the 1798 rebellion, the 1916 uprising itself has become so thoroughly mythologized and impregnated with symbolic meaning that it seems almost impossible to cut away the layers of heroic glamour and see it in more dispassionate, objective terms.

'Recent Irish historians have begun a much-needed demythologizing process: here is David Fitzpatrick, in the Oxford History of Ireland [quoting from the longer extract provided by Edward Picot]:

"Joseph Mary Plunkett and Thomas MacDonagh, like Pearse, revelled in the vulgar wartime lie that the shedding of blood was 'a cleansing and sanctifying thing'...The main victims of the 'proclamation of the Irish Republic' were...unarmed civilians, whose suffering was compounded by the wreckage of central Dublin..."

'Fitzpatrick argues that only after the English Government obliged the rebels by over-reacting to the uprising, were the ringleaders gradually transfigured into folk-heroes:

"...a sentimental cult of veneration for the martyrs developed outside as after previous failed uprisings."

'The 'sentimental cult' which came to surround the 1916 uprising certainly owed a great deal to the work of W. B. Yeats; and there can be little doubt that Heaney is following in the same tradition by making his own contribution to the 'sentimental cult' of 1798.' (See also my comments on his poem Requiem for the Croppies.)

But I think that W. H. Auden was completely correct in 'attempting to account for the fact that a better poem had been written about a small Irish uprising in 1916 than any about the whole of World War II.' (Daniel Albright, the editor of 'W. B. Yeats: The Poems.')

Irish nationalists within the British state before and during The First World War were not at all altruistic. They were preoccupied with their own plight, or their own supposed victim status (I incline to the view that the second alternative was closer to the reality.) The wider British state could be far more altruistic, as at the time of Britain's entry into the war. Gary Sheffield's 'A Short History of The First World War' is a book of exceptional insight, and he discusses well the issues which led to Britain's entry.

He writes, 'There was nothing inevitable about the British entry into the war.' There were differences of opinion amongst British politicians. Asquith, for instance, 'initially thought that Britain should stay out of the war ... And yet on 4 August, Asquith's government, with Lloyd George remaining a prominent member, brought a largely united nation into the war.

'What changed the situation was the German invasion of Belgium. Both Britain and Germany (the latter through its predecessor state of Prussia) had guaranteed the independence and neutrality of Belgium in a treaty of 1839. That a major power should simply rip up an international agreement was regarded as a moral outrage, causing genuine anger.' The anger was widely felt in Britain and, too, admiration for Belgium. There were strategic reasons for supporting Belgium, it's true. 'Maintaining maritime security by keeping the coast of the Low Countries out of the hands of a hostile power had been a staple of British foreign policy for centuries. German occupation of Belgium posed a similar threat to that of the occupation of the same territory by another naval rival, Revolutionary and Napoleonic France, a century before and provoked the same response.'

Before long, Germany was in control of almost the whole of Belgium (not the area around Ypres) and a significant part of France, a part which was rich in resources. The historiography of The First World War and its antecedents is vigorous, contested and interesting. Some influential historians have stressed the continuities between the German policies which led to the occupation of most of Belgium and a large area of France, even if the Third Reich was far more aggressive.

Gary Sheffield has an instructive section on 'The Fischer Debate:' 'One man above all has shaped the debate on the origins of the First World War over the last fifty years: the German historian Fritz Fischer ... Fischer broke the consensus that Europe slid into war in 1914 by arguing that the war was caused, in the uncompromising German title of hi first book, by 'Germany's grab for world power' (Griff nach der Weltmacht).'

It can be claimed that, as in the case of the Second World War, the Irish had a very great deal to lose in the event of a German victory and that British power was protective.It can also be claimed that analyses in terms of British 'occupation' and imperialism do no justice to these harsh realities.

It was in Britain that the industrial revolution began and it was the industrial revolution which provided the solution to endemic poverty. Nationalist Ireland lacked the inner resources to develop industrialisation itself or to accept for a long time industrialisation at a level sufficient to lessen and eventually to end poverty and gross deprivation of the worst kinds.

From Roy Foster's 'Modern Ireland: 1600 - 1972, describing the backwardness of nationalist Ireland in the later 19th century:

'The labour question in Ireland reflected the nature of Irish urbanization and Irish industry. The latter was largely a question of servicing, processing and transporting agricultural commodities; industrial development as normally conceived remained in an arrested state ... there was no parallel to the 'New Unionism' generated in Britain by large-scale industrial growth. Irish trade unions were generally rather inactive offshoots of British organizations ...

'The non-industrial base of Dublin was one of the main reasons for the precarious and extremely impoverished condition of its proletariat by the late nineteenth century ... appalled contemporaries record a bizarre and essentially pre-industrial profile of life in the lower depths ... The centre of the city was a byword for spectacularly destitute living conditions ... at the same time as Plunkett's agrarian experiments, and the narodnik search by urban intellectuals for pure Gaelic values in the far west, life went on in eighteenth-century tenements bereft of water or sanitation; Dublin retained the worst urban adult mortality rate in the British Isles; the death rate did not decline until the early twentieth century ... Living conditions were horrific by contemporary standards ...

'Yet Dublin politics remained orchestrated by the increasingly nationalist Corporation, dominated by small manufacturers, grocers and publicans, and fixed on the iniquity of British rule rather than the shortcomings of social organization in the city ... The government of the city never applied successfully for special grants from central funds; no 'civic gospel' suggested that a programme of urban renewal would constitute an appropriate activity for the Corporation.'

...

Vested interests meshed with political apathy: Catholic nationalism, in the form of bishops as well as politicians, was firmly dedicated against committing any future Home Rule state to burdens of social expenditure and secular welfarism. Energetic representations from pressure-groups could not enforce a commitment to tenement clearance or rebuilding ...'

No transformation in history is as important as the British industrial revolution, which quickly transformed more receptive nations, such as Belgium, but not others, such as Ireland. Why do far fewer women die in childbirth, why do few people in industrialised nations live amidst vermin, unable to feed themselves adequately or to keep warm, why do people in industrialised nations not live in insanitary cabins?

E A Wrigley gives this useful summary of the impact and benefits of the Industrial Revolution in 'Energy and the English Industrial Revolution:'

'One of the best ways of defining the essence of the industrial revolution is

to describe it as the escape from the constraints of an organic economy.

Civilisations of high sophistication developed at times in many places in

the wake of the neolithic food revolution: in China, India, Egypt, the

valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates, Greece, and Rome, among others. Their

achievements in many spheres of human endeavour match or surpass those of

modern societies: in literature, painting, sculpture, and philosophy, for

example, their best work will always command attention. Some built vast

empires and maintained them for centuries, even millennia. They traded over

great distances and had access to a very wide range of products. Their

elites commanded notable wealth and could live in luxury. Yet invariably the

bulk of the population was poor once the land was fully settled; and it

seemed beyond human endeavour to alter this state of affairs.

'The 'laborious poverty', in the words of Jevons, to which most men and

women were condemned did not arise from lack of personal freedom, from

discrimination, or from the nature of the political or legal system,

although it might be aggravated by such factors. It sprang from the nature

of all organic economies. [In organic economies] .. plant growth ...

represented the bulk of the sum total of energy which could be made available

for any human purpose. The other energy sources which were accessible,

chiefly wind and water, were, comparatively speaking, of minor importance.

The ceiling set in this fashion to the quantity of energy which could be

secured for human use was a relatively low limit because only a tiny

fraction of the energy reaching the surface of the earth from the sun was

captured by plant photosynthesis. Since all productive processes involved

the consumption of energy, and plant growth was the dominant energy source,

the productivity of the land conditioned everything else.

...

'The process of escape was slow but progressive ... from being a minor

contributor to energy supply in Tudor times, coal increased steadily in

importance, reaching a position of almost total dominance by the

mid-nineteenth century.'

'By

the waters of Doo Lough we lay down and slept ...' Poem from my page Poems:

By the waters of Doo Lough we lay down and slept,

and all our prayers were answered at once,

Mary, Mother of God, be thanked -

for an end to the sleet,

the unendurable sleet,

an end to the hunger

that gnawed our bones,

the unendurable hunger,

an end to our lives,

their unendurable lives.

On 30 March, 1849, hundreds of starving people applied for famine relief in Louisburgh, County Mayo. They were ordered to report to the Westport Poor Law Union at Delphi, ten miles to the south, at 7 a.m. the next day. They walked through the night, in rain, sleet and snow. They were refused famine relief and began the walk back. By Doo Lough, an unknown number died. An annual famine walk from Louisburgh to Doo Lough commemorates the event. The first line of the poem recalls the first line of Psalm 137, 'By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down and wept ...'

The lines in this poem of mine are spoken by a single person except for the lines in italics, which are spoken by a number of people, perhaps members of an audience. This recalls the words of the priest and the responses of the congregation. The series is intended particularly to give opportunities for performance and interpretation to the people attending a poetry reading, to make their role far more of an active one. There should preferably be practice, rehearsal, directed at changes of tempo, the giving of weight to the words, variations in weight, above all reaching towards the bitterness and tragic intensity of the experience.

Irish famine: Black and White

The

trees were barely white.

The sky was largely grey.

The stored potatoes turned black.

That winter, all the family starved.

The children were buried in potato sacks.

This extended quotation, on agriculture, industry and famine, is taken from my page on Radical Feminism. (The page has an extended section on 'the material conditions of life' which is relevant as well.) Britain's response to The Great Famine in the mid-nineteenth century was worse than inadequate, but Britain had this to its credit. It was the place where The Industrial Revolution began, where so many of the inventions and innovations which transformed life were devised, the place where for a long period of time The Industrial Revolution was most vigorous by far. There wasn't one famine in history, of course, which dwarfed all other famines, this period of famine in Ireland. By then, there had been famines in every country in the world, very often less severe, sometimes more severe. It was The Industrial Revolution which ended the threat of famine in industrialised countries. When Ireland eventually became an industrialised country itself, it was with British help.

'On the back cover of Peter Mathias's 'The First Industrial Nation:' 'The fate of the overwhelming mass of the population in any pre-industrial society is to pass their lives on the margins of subsistence. It was only in the eighteenth century that society in north-west Europe, particularly in England, began the break with all former traditions of economic life.'

'In the 'Prologue,' this is elaborated: 'The elemental truth must be stressed that the characteristic of any country before its industrial revolution and modernization is poverty. Life on the margin of subsistence is an inevitable condition for the masses of any nation. Doubtless there will be a ruling class, based on the economic surplus produced from the land or trade and office, often living in extreme luxury. There may well be magnificent cultural monuments and very wealthy religious institutions. But with low productivity, low output per head, in traditional agriculture, any economy which has agriculture as the main constituent of its national income and its working force does not produce much of a surplus above the immediate requirements of consumption from its economic system as a whole ... The population as a whole, whether of medieval or seventeenth-century England, or nineteenth-century India, lives close to the tyranny of nature under the threat of harvest failure or disease ... The graphs which show high real wages and good purchasing power of wages in some periods tend to reflect conditions in the aftermath of plague and endemic disease.'

'Larry Zuckerman, 'The Potato:' 'Famine struck France thirteen times in the sixteenth century, eleven in the seventeenth, and sixteen in the eighteenth. And this tally is an estimate, perhaps incomplete, and includes general outbreaks only. It doesn't count local famines that ravaged one area or another almost yearly.'

Christian Wolmar's 'Blood, Iron and Gold: how the railways transformed the world' includes this, after pointing out one way in which diet was improved by the coming of the railways: 'There were countless other examples of the railways improving not only people's diets but their very ability to obtain food. France, for example, had periodically suffered famines as a result of adverse weather conditions right up to the 1840s, but once the railways began reaching the most rural parts of the country food could easily be sent to districts suffering shortages. Moreover, it would be at a price people could afford ... The consumption of fruit and vegetables by the French urban masses doubled in the second half of the nineteenth century almost solely as a result of the railways.'

An isolationist interpretation of the Great Famine will focus attention on the callousness of the English response. A ((survey)) will take account of that but also such a factor as the incalculable benefits of the railway revolution, which began in this country. Christian Wolmar quotes Michael Robbins: 'Until about 1870 ... Britain was the heart and centre of railway activity throughout the world.' Writers on the evils of English colonialism have generally failed to acknowledge these incalculable benefits. Their ((survey)) has been defective.

The rebellion of 1798 which ended in the defeat of the rebels at Vinegar Hill is the subject of Seamus Heaney's poem Requiem for the Croppies which I analyze and discuss in detail. (My discussion of his poem Wolfe Tone contains material on this period as well.)

'The rebels themselves committed atrocities, like their opponents. The ferocity of the rebels was more than matched by the reprisals against them. Tony Geraghty describes atrocities 'against unarmed Protestant captives and civilian hostages. At Sullabogue, a barn crowded with 200 people, including children, was torched.

'Musgrave, piercing the evidence together three years later, concluded that 184 Protestant prisoners were burned inside the barn and thirty-seven shot in front of it.'

'Tony Geraghty describes further atrocities at Wexford, including this: 'With the rebels in retreat, they had to abandon the town of Wexford. Their parting gesture was a massacre on the bridge across the River Slaney, near its estuary, on 20 June ... The historian Lecky (supported independently by Musgrave) concluded that ninety-seven people died, stabbed with pikes and flung into the river.' ('The Irish War.')

Desperate people don't, usually, have a wide choice of potential helpers, from the very enlightened to the very unenlightened. The rebels chose France. France was aggressive and militarist, if in a more high-minded way than than some other aggressive and militarist states have been. France declared war on Austria and Prussia in 1792 and on Britain and Holland in 1793. In his essay, 'Place and Displacement: Recent Poetry from Northern Ireland,' Seamus Heaney writes, 'When England declared war on Revolutionary France, Wordsworth experienced a crisis of unanticipated intensity ....' but this is incorrect. It was France that declared war on Britain, on 1 February 1793.

France was not only the enemy of Britain, it would also have been, in time, the enemy of Ireland. There's no indication at all that a victorious France would have been more enlightened in its relations to Ireland than Britain. The suffering that Napoleon brought to Europe was enormous. David Gates estimated that about 5 million people were killed during the Napoleonic wars (in his book 'The Napoleonic Wars.') Charles Esdaile estimates that between 5 and 7 million people, troops and civilians, were killed. (Napoleon's Wars: An International History.') Napoleon was an aggressive invader of other countries. Britain feared invasion by Napoleon and prepared against it. If Napoleon had not been defeated, it's very likely that he would have invaded Britain and that if he had been successful, he would have added Ireland to his list of conquests. The rebels of 1798 looked for help to France and the rebels of 1916 looked for help to Germany. Both appeals, for a Britain with survival at stake, amounted to treachery. All these considerations of international power politics are uncomfortable but inescapable.

The rebels were following the lead of a secret society, the United Irishmen. From 'Ireland's Holy Wars,' by Marcus Tanner: '... while radical Protestants were thick on the ground among the intellectual leaders of the United Irishmen, they were thinly represented at the other end ... The leaders might preach the secular nationalism of the French Revolution. The ordinary pikemen were motivated by an age-old hatred of Protestants of all classes ... the rebels called their prisoners 'heretics.' '

David A Bell, in his very impressive book 'The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Modern Warfare' has a chapter on the rebellion in the Vendée in 1793 - 1794. He mentions the killing in Southern France after the Protestant revolt of 1702 - 4 and in the Highlands of Scotland after the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, but he writes 'the Vendée, however, occupies a different dimension of horror.' It occupies a different dimension of horror from the rebellion of 1798 as well. In the Vendée, 'According to the most reliable estimates, from 220 000 to 250 000 men, women and children - over a quarter of the population of the insurgent region - lost their lives there in 193 - 94. The principal campaign against the Vendée's "Catholic and Royal" peasant armies, [Compare the predominantly Catholic, peasant armies of the Irish rebellion] which lasted from March to December of 1793, set a new European standard in atrocities. Then, at the start of 1794, the Republican general Louis-Marie Turreau sent twelve detachments of two to three thousand soldiers each marching across the territory in grid fashion, with orders to make it uninhabitable. These "hell columns" burned houses and woods, confiscated or destroyed stores of food, killed livestock, and engaged in large-scale rape, pillage, and slaughter. In some cases they killed only suspected rebels. In others, as at La Frocelière, they liquidated men, women and children indiscriminately, including "patriots" who had remained loyal to the Republic, on the grounds that no one still living in the Vendée could truly be loyal. In the port city of Nantes, the Republican authorities devised appalling new methods of mass murder to eliminate the "brigands" more efficiently and to reduce stress on the killers. Most hideously, they lashed thousands of prisoners into barges and lighters, which they then towed out into the Loire estuary and sank.'

'Writers favorable to the Revolution, meanwhile, while deploring "excesses," have insisted that horrors were committed on both sides and that the insurgents did, after all, side with France's enemies during wartime.' I'm not in the least an apologist for the Britain which quelled the Irish rebellion of 1798 but it's true that horrors were committed by both the British and the Irish and that Irish insurgents sided with Britain's enemy, France, during wartime. The France they sided with was the state which had perpetrated these atrocities.

The relevance of this to Ireland, not just the action taken against Roman Catholicism but the pikes and scythes of the peasants (compare Seamus Heaney's Requiem for the Croppies) will be obvious: 'In many of the more isolated areas, the Revolution's subjection of the Catholic Church to secular state authority cut deep into the tissue of communal life, with villages enraged at the dismissal of long-serving priests. In reaction, bubbles of anxiety and rage burst angrily on the surface of rural life. The most serious rioting took place after the fall of the monarchy in the fall of 1792, when crowds of peasants armed mainly with pikes and scythes occupied several towns in the region, leading to fighting that left up to a hundred dead.' The parallels extend too to the tactics of the rebels. 'Even after capturing several cannon, they rarely managed to stand in formal, pitched battles against the Republican forces. They preferred ambushes in the broken up and overgrown terrain and sudden, frenzied charges ...'

'What sustained them, above all, was religion. Witnesses described them marching in solemn silence, telling rosary beads, stopping for prayers, and crossing themselves before charging into combat. Priests accompanied them and before battles gave out remissions of punishments for sin.'

Like the croppies, the rebels in the Vendée committed atrocities themselves. 'Both sides routinely put captured enemy soldiers to death. Each side justified its conduct by reference to the other. The Irish rebels looked for help from France, the enemy of Britain. The French rebels looked for help from Britain, the enemy of France. They retreated towards the English channel, in 'a forlorn attempt ... to open a French port to the British navy, which had been seeking one since France and Britain had gone to war in the spring.'

'The remnants of the Catholic and Royal Army made a futile last stand near the village of Savenay, on December 23, and were annihilated.' This was the rebels' battle of Vinegar Hill. Westermans wrote to the authorities in Paris, 'I do not have a single prisoner with which to reproach myself.' But the killing of the rebels went on and on after the annihilation of the rebels' army.

English misrule In Ireland was a fact, but it's easy to forget - Seamus Heaney certainly finds it easy to forget - that enlightened rule was very scarce in the eighteenth century, as in other centuries.

In 'Irish Freedom: the History of Nationalism in Ireland,' Richard English writes, 'Much of the old orthodoxy regarding eighteenth-century Ireland has now been reconsidered in scholarly analysis: stark assumptions concerning the supposedly appalling oppression of Catholics, the antagonism between aristocracy and peasantry, the idea of English misrule as the cause of Irish economic problems, or even the colonial quality of the Irish-English relationship itself - all of these have been questioned to some degree.'

If the English had failed to defeat the rebels, historically almost impossible, and failed to defeat Napoleon, not at all impossible, if the rebels had set up a nationalist Roman Catholic state, it's historically probable that Napoleon, the secularist and enemy of such states, would have turned his attention to it and invaded. The armed forces of this new Irish state would have opposed him and been crushed.

'By 1812 France held effective sway over nearly the entire European continent, excluding the British Isles, Scandinavia, Russia, and the Turkish empire. Most of the territory either fell under the direct rule of Paris or belonged to an ally or satellite state ... ' (David A Bell, 'The First Total War.') There were insurrections against French control between 1806 - 10 but it was in Spain that resistance to French control was greatest, where the fighting was most bitter, the atrocities the worst, the number of those killed the greatest. Goya illustrated some of the atrocities - the executions in Madrid in 1808 (Tres de Mayo) and the atrocities carried out by both sides in his etchings, 'The Disasters of War.' During the siege of Saragossa in 1808 the French bombarded the city with more than 40 000 explosive shells, the city still refused to surrender, the French broke in and 'there then began some of the worst urban combat ever seen in Europe before the twentieth century, ' but as was the norm in war before the twentieth century, more people died of disease than from shells, mines and small arms.

Saragossa eventually surrendered but in the Spanish countryside, guerilla war went on. It was their Roman Catholic religion which gave the guerillas their absolute enmity towards the French. The priests, monks and nuns preached against the French at every opportunity. A Spanish catechism of 1808 called the French 'former Christians and modern heretics' and remission from punishment for sin was promised to those who fought against them. It's a safe assumption that for Irish Catholics as well as Protestants, British control was a lesser evil than French control would have been. It's also a safe assumption that at this time in history, Ireland would not have had a great chance of being left unmolested as a peaceful, free and independent state.

The very harsh suppression of Catholicism by Britain during the earlier period of British rule of Ireland, the massacres of Catholics by the British - few in number, but atrocious - the whole of this shameful period of history, have been viewed in complete isolation by too many commentators on Seamus Heaney. The missing context includes the long era of religious intolerance in Europe during which Protestants executed Catholics and Catholics executed Protestants, by burning alive, hanging drawing and quartering, and other methods, during which Protestants massacred Catholics and Catholics massacred Protestants, during which Protestants imposed severe restrictions on the life of Catholics and Catholics imposed severe restrictions on the life of Protestants. The Christian killing of individuals shouldn't be forgotten either. Ludovic Kennedy, in 'All in the Mind: a Farewell to God' writes about an execution in France in 1766: '... the young Chevalier de la Barre was walking along a street in Abbeville. A Capuchin religious procession passed by. Because it was raining the chevalier did not doff his hat as was then the custom. This was observed and reported on, and the chevalier was arrested. The charge against him was blasphemy. He was found guilty. The sentence of the court was amputation of the hands, the tongue to be torn out with pincers and then for him to be burned alive ... Voltaire said he was haunted by the story for the rest of his life.'

When Christianity became less powerful, when Christians began to lose their taste for repressing and killing other Christians and repressing and killing non-believers, the repression and killing carried out by Moslems and non-believers (who have tortured and killed on a massive scale) ensured that there was no end, no slackening, of humanity's atrocious record of inhumanity. Secularism has brought many benefits, but not, unfortunately, an end to ideology or an end to bloodshed. (In all this, it's obvious, of course, that I'm referring to some Christians, some Moslems and some non-believers, not all. )

This, then, is the harsh context of the sufferings of Catholics at the hands of the Protestant British.

One massacre among many, recounted by Michel de Waele, at

http://www.blackwellreference.com/public/tocnode?id

=g9781405184649_chunk_g97814051846491300

'The St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre was one of the bloodiest events of the Wars of Religion that shook France from 1562 to 1598. Catholics in Paris killed between 2,000 and 4,000 Protestants between August 24 (St. Bartholomew's Day) and August 30, 1572, and then thousands more in various provincial towns between August 24 and October 6. Estimates of the total number of Protestants massacred in France during that period vary from 10,000 to 100,000.The conflict was not purely religious; its roots were primarily social and political. The aristocracy in France was deeply split into two rival parties, one of which adopted Calvinism as an ideology with which to challenge its Catholic opponents. As the conflict deepened, the religious identities solidified, and as the two noble factions enlisted support among other segments of the population, the struggle evolved into fullblown civil war between Catholic and Protestant (Huguenot) communities.'

A later conflict, The Thirty Years War, which devastated large areas of Central Europe and above all Germany between 1618 and 1648, had social and political aspects but it was a religious war too, and again, Protestants killed Catholics and Catholics killed Protestants in enormous numbers. Almost a third of the 15 million people in Germany perished.

The responsibilities of critics are different from those of poets. The 'much-needed demythologizing' of Irish History which recent Irish Historians have carried out is in stark contrast with 'the much-needed demythologizing' of Seamus Heaney and many other poets, past and contemporary, which critics haven't attempted. And many critics haven't made use of demythologized Irish History in their interpretations of Seamus Heaney, but a tired and routine history to go with their tired and routine criticism, perpetuating questionable or indefensible claims.

Credit: Creative Commons Link to licence

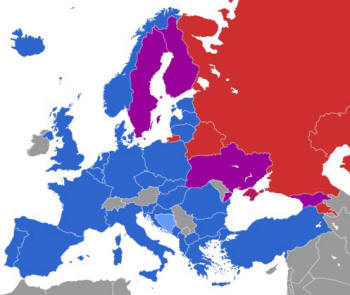

Top image: Irish nationalist banner. Image with slogan 'NAZI GERMANY GET OUT OF IRELAND.' An example of hypothetical history: what might have happened if Great Britain hadn't been successful in defending the whole of the British Isles, including the Republic of Ireland, against Nazi invasion: the hypothetical slogan on an Irish nationalist banner during the Second World War following Nazi Invasion of Ireland. The banner would have had no effect. The Nazis would have remained in power and everyone involved in producing or using the banner would most likely have been executed. Two images concerned with Ireland and NATO, with a map showing NATO members.

What I call 'hypothetical history' is referred to as 'virtual history' in the exceptionally interesting - outstanding - book with the title 'Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals,' edited by Niall Ferguson. It contains an exceptionally interesting - outstanding - chapter by Andrew Roberts, 'Hitler's England: What if Germany had invaded Britain in May 1940?' It contains this, ' ... how close in reality did a German invasion and occupation of Britain actually come?' This could be extended: ' ... how close in reality did a German invasion and occupation of the British Isles actually come?' If the Nazi forces had invaded and occupied Britain, the invasion and occupation of the Irish Republic would have presented no difficulties.

From the section on this page The Second World War, which is about non-hypothetical history, including harsh realities which Irish nationalists in general refuse to acknowledge:

There are startling gaps and omissions in the Irish nationalist view of history. The most important single omission is The Second World War - not, obviously, a minor one. According to the mythology of Irish nationalists, nobody has suffered like the Irish, nobody has exploited others like the English. But in a conflict which was more devastating than any other in history, which inflicted suffering on a greater scale than any other, the English, and the other countries of the United Kingdom, including Northern Ireland, a constituent part of the United Kingdom, carried on the war against Hitler alone, for a time, with exiled groups from many countries and volunteers from many countries, including volunteers from the Irish Republic, who served in large numbers. Irish nationalism and the Irish Free State stood aside and did nothing. The IRA actively sought help from the Germans. During The Second World War, the Irish Free State was neutral. After the death of Hitler, condolences were offered from only two sources, Portugal and the government of The Irish Republic. 'The Cruel Sea' is a popular novel by Nicholas Monsarrat.' The factual claims here are confirmed by Brian Girvin in his scholarly 'The Emergency: Neutral Ireland 1939 - 1945).

'...it was difficult to withhold one's contempt from a country such as Ireland, whose battle this was and whose chances of freedom and independence in the event of a German victory were nil. The fact that Ireland was standing aside from the conflict at this moment posed, from the naval angle, special problems which affected, sometimes mortally, all sailors engaged in the Atlantic, and earned their particular loathing.

'Irish neutrality, on which she placed a generous interpretation, permitted the Germans to maintain in Dublin an espionage-centre, a window into Britain, which operated throughout the war and did incalculable harm to the Allied cause. But from the naval point of view there was an even more deadly factor: this was the loss of the naval bases in southern and western Ireland, which had been available to the Royal Navy during the first world war but were now forbidden them. To compute how many men and how many ships this denial was costing, month after month, was hardly possible; but the total was substantial and tragic.

'From a narrow legal angle, Ireland was within her rights: she had opted for neutrality, and the rest of the story flowed from this decision. She was in fact at liberty to stand aside from the struggle, whatever harm this did to the Allied cause. But sailors, watching the ships go down and counting the number of their friends who might have been alive instead of dead, saw the thing in simpler terms. They saw Ireland safe under the British umbrella, fed by her convoys, and protected by her air force, her very neutrality guaranteed by the British armed forces: they saw no return for this protection save a condoned sabotage of the Allied war effort: and they were angry - permanently angry. As they sailed past this smug coastline, past people who did not give a damn how the war went as long as they could live on in their fairy-tale world, they had time to ponder a new aspect of indecency. In the list of people you were prepared to like when the war was over, the man who stood by and watched while you were getting your throat cut could not figure very high.'

The Irish Republic is one of many freeloaders, one of the many countries which do hardly anything to defend themselves. They rely on other countries to maintain their security. However, none of the countries whose defence expenditure (as a percentage of GDP) is given has a defence expenditure as low as the Irish Republic's.

Military expenditure (% of GDP) in Ireland was reported at 0.2899 % in 2019, according to the World Bank collection of development indicators, compiled from officially recognized sources.

The police force and the armed forces are primary responsibilities of government: protection against internal threats and protection against external threats. The Irish republic has an effective police force but its defence forces are pitifully inadequate. It makes next to no attempt to contribute to collective security. Like so many European countries, its defence expenditure is a tiny proportion of GDP. It isn't a member of NATO. In a dangerous world, with threats from Russia and the deranged Iranian regime, which threatens the supply of oil to Ireland as well as Britain, it relies for its protection upon Britain, the United States and other countries which take seriously defence of the non-totalitarian world.

Below: NATO members in Europe shown in blue. Missing: the Irish republic. Membership of NATO would have symbolic importance, it would demonstrate that it takes the threat of Russian aggression seriously and has a serious interest in contributing to collective security, even if its armed forces would make a negligible contribution, but too many people in the Irish republic are more interested in historic grievances than present day realities.

Above, views of Ben Bulben, County Sligo. Above all, Ben Bulben is a

magnificent mountain. I count myself fortunate to have seen the actual

mountain and not just photographs of the mountain, during my visits to

Ireland, the North and the South. It's not only in Ireland that mountains

and other scenic wonders have linkages with politics but Ben Bulben and its environs

have close linkages with the politics of Ireland, North and South.

Events which have a linkage with Ben Bulben from more recent to less recent,

in accordance with the organizing principle of this page:

On 20 September 1922, during the Irish Civil War, an IRA column, including an armoured car were cornered in Sligo. The car was destroyed by another armoured car belonging to the Irish Free State's 'National Army' and six of the IRA soldiers fled up the Ben Bulben's slopes. In the end, all were killed, allegedly after they had surrendered

Brigadier Seamus Devins TD, Div. Adj. Brian MacNeill, Capt. Harry Benson, Lieut. Paddy Carroll, Vols. Tommy Langan and Joe Banks were those killed on the mountain. The six anti-treaty fighters were hunted down on the slopes of Benbulbin and put to death by Free State forces which were out to avenge the killing of Brigadier Joseph Ring eight days earlier.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Sinn Féin had engaged in a campaign which made use of the slogan, 'Brits out of Ireland'. The slogan was daubed on walls all over Ireland and in 1977, Ben Bulben was defaced, with the slogan .'Brits Out' (180 ft wide and 25 ft high) and ater with the slogan 'H-Block'.

Ben Bulben overlooks the village of Mullaphmore, the site of the assassination of Lod Mountbatten in 1979. Among those killed at the same time were two boys, 14 years old and 15 years old. The killings gave rise to outrage throughout the world.

At that time when the Irish Republic stood aside and took no part in the fight to overcome Nazism - although people from the Irish Republic did volunteer and joined the allied forces:

During World War II there were two plane crashes in the Dartry mountains near to Ben Bulben. On 9 December 1943, a USAAF Boeing Flying Fortress plane flying from Goose Bay, Labrador to Prestwick, Scotland crashed just east of Ben Bulben. 10 airmen were aboard, of whom three died, two at the scene and one from injuries sustained in the crash.

Nearby, on 21 March 1941, an RAF Catalina flying boat crashed. All nine airmen aboard died in the crash.