See also

Bullfighting: arguments against and action

against

Review

of A L Kennedy: 'On Bullfighting'

Veganism: arguments against

Ethics: theory and practice

Supplementary material below is in italics

The material here is very varied, including a discussion: Animal rights activists: distortions and illusions.

Our arrest was sudden and unexpected but not dramatic. I was walking with another activist in the city centre, a police car came to a stop, without any screeching of brakes, and within a few moments we were inside the car. The experience didn't feel very momentous. A complete contrast with the description in Chapter 1 of Solzhenitsyn's 'The Gulag Archipelago.' Solzhenitsyn didn't exaggerate, of course: this was Stalinist Russia:

'Arrest! Need it be said that it is a breaking point in your life, a bolt of lightning which has scored a direct hit on you? That it is an unassimilable spiritual earthquake not every person can cope with, as a result of which people often slip into insanity?

'...If you are arrested, can anything else remain unshattered by this cataclysm?

'But the darkened mind is incapable of embracing these displacements in our universe, and both the most sophisticated and the veriest simpleton among us, drawing on all life's experience, can gasp out only: "Me? What for?" '

The two of us were told by the arresting officers exactly 'what for.' 'Going equipped for criminal damage, possession of paint to attack fur coats.'

The ride to the police station didn't take long. Conversation flagged on the way. The silences weren't too awkward, though. At the station, I was put in a cell on my own and the door clanged shut.

Initial impressions were very favourable. The cell was immaculate. I explored the cell. There wasn't a great deal to explore. I found en-suite toilet facilities, again, scrupulously clean. If ever I write a 'Good Cell Guide' I'd give this cell four stars. There weren't the inconveniences of a one-star cell: grey hordes of lice waiting to leap out and fasten their jaws on you, cockroaches scuttling across the floor, fresh or faded bloodstains on the walls, graffiti scratched laboriously, "Liberty or death!" nothing but toilet paper available on which to write poetry (although I suppose that usually, toilet paper isn't available in a one-star cell), thuds and screams from a neighbouring cell, from further off last shouts of defiance, a volley of shots followed by the crack of the coup de grace. There weren't twenty or so others crammed in the cell. Instead, silence, and that clinical spotlessness. The only thing that put me off was the bench - hard, unyielding, uncompromising. Not a thing you'd wish to lie on for a life sentence. A five-star cell would have a softer bench and perhaps a chair even (bolted to the floor, obviously, so a prisoner couldn't throw it at the members of staff.)

Some years before I stayed in a four-star cell, I worked in a four-star hotel as a night porter. (My employment history is quite varied. It includes work as a builder's labourer. Before I worked in the hotel, I'd spent a year working as a nursing assistant in a hospital, which taught me all I need to know about wiping the bums of geriatric patients. I have to say that many of the things I witnessed in a professional job were far more off-putting - I'm referring to the 'system,' not the clients.)

The experience wasn't nearly as interesting as George Orwell's work in hotels, recounted in 'Down and Out in Paris and London.' Any guests who wanted their shoes polishing left the shoes outside the door in the corridor. I was asked to leave my shoes outside the door of this four star cell. I don't think I was asked to leave them there so that the police could polish them for me. I speculated as to the reason. I vaguely remembered something about prevention of suicide - to prevent inmates hanging themselves with their own shoelaces. But hanging myself with my own shoelaces has never appealed to me.

One thing about the comforts of the hotel rooms, spiritual comforts in this case. The group known as the 'Gideons' provided Bibles in various places. In this hotel, every room had a Gideon New Testament and Psalms. The reckless generosity of the Gideons didn't extend to the full work. But in the cell, there was nothing from the Bible at all. I would have expected the Gideons to understand that the dark night of the soul, the desolation of the human spirit, was more likely in a cell, no matter how wonderful the cell, than in a four star hotel.

I'd make a plea for the full works, the complete Bible. It would be a great pity if prisoners were to be denied the resources of Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. There are many religious groups and organizations whose members believe that the Bible is the Word of God, all of it, but in practice, they badly neglect some of scripture. Robert Graves recounts a sermon in his First World War memoir 'Goodbye to all that.' The sermon was about an obscure topic, the commutation of tithes, 'Quite up in the air, and took the men's minds off the fighting.' Reading about the commutation of tithes or the curtains of the tabernacle or the Urim and the Thummin or 'A repetition of sundry laws' would be better than staring at the door or the walls or the ceiling or the floor of this cell.

I've known far worse conditions in freedom. Once, a long time ago, in my teeenage years, when my money ran out in Ayr, I was forced to follow in the footsteps of George Orwell again and stay in a hostel for down and outs. It was called 'The Trades Hotel.' This was its real name, not a name given to it by humourists, even though anyone in a trade would have done anything to avoid it.

I only had sliced white bread and margarine to eat and as I didn't have a knife I smeared the margarine over the bread by hand. The sleeping arrangements were these: a hundred or more men in one very large room, each one in a tiny cubicle. I asked someone why there was wire netting over the cubicles. It was to stop objects landing on you when anyone felt like throwing them. Sleep-preventing coughs, singing of only a modest standard and the blowing of a trumpet - much more accomplished - punctuated the long nights. There were sheets and even a pillow case, but they were rigid with dirt and when I came back home I had to have treatment for the flea bites that covered my body. A few years after I was a guest there, the place burned down with the loss of six lives.

Before long, a police officer came to the little opening in the door of the cell, opened the flap and said something or other. All I can remember is the phrase 'When you appear in court.' If this was an attempt to unsettle me, to make me panic, it didn't have the desired effect. I've done nothing wrong! I'm completely innocent!

After two hours, it was clear that the police agreed that I didn't intend to commit criminal damage. We'd been searched, nothing had been found. We were released and able to experience again that blissful state, comparative freedom. I didn't gain a criminal record, and still don't have one. The experience had disadvantages. The most obvious one is that being arrested can make it harder to enter the U.S. Even if you've done nothing wrong, it can count against you. As I've no compelling reason to re-visit The Land of the Lethal Injection, this doesn't matter. My page on the death penalty includes more on, praise for America as well as criticism of American backwardness.

A few days after my release, I joined Amnesty International. One of

the novels which means the most to me is Kafka's 'The Trial.' (My page

Kafka and Rilke gives an appreciative,

analytical discussion of Kafka.) Before long, I

was doing work in the field of human rights and did so for a very long time,

using methods very different from the militant methods I'd taken part in for a

short period, completely mistakenly - I was young, but old enough to know

better - writing

to governments, boards of pardon and parole and other offenders, helping to

raise funds. I've taken part in protests in the field of animal welfare since

then but they have all been non-abrasive (apart from one I started myself in

the bullfighting town of Arles.) After the material on animal welfare/animal

rights: supplementary material on the death penalty.

To return to my case, the false allegation that the two of us were carrying paint to deface fur coats came from the manageress of a fur department in a department store. We were members of a group which in a short space of time succeeded in closing down every fur department but one in the city. (The exception was visited by the stupid Animal Liberation Front and closed after that.) If the manageress feared for her job, she may have been right.

The main tactic was for forty or so activists to descend on a fur department, sit down and refuse to leave, as simple as that. Subjecting the department store to intense inconvenience and unfavourable publicity. I'm sure that these tactics were badly mistaken, that I was badly mistaken in taking part, that I should have confined myself to persuasion and argument.

We also arranged a couple of demonstrations outside the stores. I addressed a very large crowd of activists, shoppers and police through a megaphone, giving an outspoken account of the shame of the fur trade. I think that these demonstrations too were mistaken. The tactic which ought to have been employed was simply the holding of low-key demonstrations outside stores, handing out leaflets. The fur trade was in rapid decline in this country, in places where large demonstrations inside and outside stores were not taking place. The battle of ideas was being won.

What of the issues? I do claim that I did everything I could to investigate these issues, to ensure that my position was based on exhaustive evidence. My information about the fur trade came amongst other sources from the book 'Facts about Furs,' by Greta Nilsson and others, published by the Animal Welfare Institute and distributed in this country by the RSPCA. Of course, it's written from a particular perspective, but the accumulation of evidence, the detailed statistics, the many references, the examination of legislation in a great variety of countries, the fair-minded attempt to state and address the arguments of the pro-fur lobby - all of these are very impressive. The book even contains, in the Chapter on 'Alternatives to Fur,' a detailed examination of the energy costs of fake fur, trapped fur and ranched fur prepared by an engineer at the Scientific Research Laboratory of the Ford Motor Company in Michigan. He calculates that the energy costs of a real fur coat in the units he uses, BTU (1BTU = 1.055kJ) is 433 000, more than three times that of a fake fur (120 300 BTU), whilst the energy costs of a ranched fur are very much greater (7 965 800 BTU.)

The images in the book are shocking, but the book doesn't make the mistake of suggesting that an image can be any substitute for rational argument, the presentation of evidence, although now, when I'm no longer involved in the struggle to end the fur trade, the images do linger in the mind particularly. Above all, the images which show the cruelties of the leghold trap (banned in this country in 1958 but still permitted in most American states and Canada): a beaver which chewed off both its front paws to escape the leghold trap, a raccoon hanging by one leg from a trap, a large hole dug by a badger trying to escape a leghold trap, a coyote dead of apparent starvation in a trap, an animal with all its teeth broken, its jaw bone eroded in the struggle to escape, a golden eagle, a swan and many pets caught, losing limbs or their lives, a bobcat with protruding bones, a trapper killing a coyote by trampling on it. Methods of killing trapped animals aren't regulated in most American states. The cruelties involved in farmed fur are less obvious but real - keeping animals in barren cages until the time comes for their asphyxiation, and all for a completely unnecessary product.

The organization which played a more important part than any other in consigning the fur trade in this country to its present marginal existence was Lynx, which was founded by Mark Glover and Lynne Kentish. The personal cost was very high. Mark Glover's work against the fur trade brought him to bankruptcy. The very large meetings organized with meticulous efficiency by Lynx publicized the issue dramatically, memorably, without recourse to mistaken tactics, at a time when fur-wearing was quite common.

At this same period, I travelled the country to take part in demonstrations, very large demonstrations, to oppose factory farming and other abuses of animals.

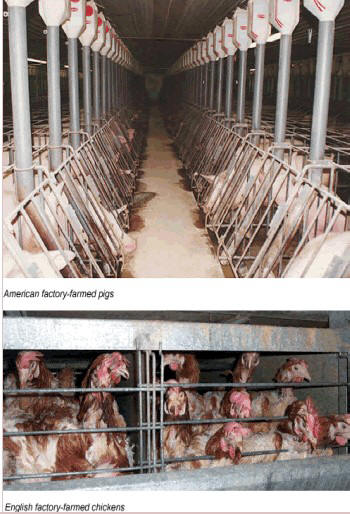

The demonstration against Lightwater Valley in Yorkshire had a particular impact. We saw rows of pigs, in clean but barren compartments, with no room to turn: a completely indefensible way to keep an animal. It wasn't, as might have been expected, hidden from view, out of shame, but open to the public, intended for family visits. But bad as conditions were, it was after all a kind of show home for factory farms. Others, not open to the public, inflict the same cruelty of close confinement, the thwarting of an animal's needs, but in conditions which are worse, not simply barren but filthy, physically disgusting as well as morally disgusting. A battery hen, a broiler hen, a pig living in an intensive unit, suffer conditions which may be more extreme than the ones on the Mississippi death row, and of course, all the animals are on death row as well, although they lack the Mississippi prisoners' knowledge of the plans made to kill them.

One of these demonstrations was organized and led by Peter Roberts, a remarkable man, one of the greatest of animal welfare campaigners. He's the founder of Compassion in World Farming, which campaigns against factory farming. He died in 2006.

Of course, then, as now, people who wanted to attend a demonstration could attend a demonstration. There were always people attending these demonstrations who weren't an asset to the animal welfare movement. Peter Roberts did his best to put a stop to one moronic chant, endlessly repeated: 'XY - whatever the name was - torture town, burn, burn burn it down!' And there was the chant 'What do we want? Animal Liberation! When do we want it? Now!'

Now? This minute?

Supplementary material on the death penalty:

I received an email which originated with Amnesty International about

conditions in Mississippi at the State Penitentiary. It puts my own very short

and pleasant incarceration in context:

'Over recent years, conditions on Mississippi’s death row have been severely criticized, including in relation to the psychological impact of these conditions and the poor mental health care provided. In May 2003, a federal judge ruled that the conditions in the State Penitentiary offended “contemporary concepts of decency, human dignity and precepts of civilization which we profess to possess”. Judge Jerry Davis found that death row inmates were being subjected to “profound isolation, intolerable stench and filth, consistent exposure to human excrement, dangerously high temperatures and humidity, insect infestations, deprivation of basic mental health care, and constant exposure to severely psychotic inmates in adjoining cells.” Among other things, the federal judge found that: the filthy conditions impacted on the mental health of inmates; the probability of heat-related illness was high for death row inmates, particularly those suffering from mental illness who either did not take appropriate steps to deal with the heat or whose medications interfere with the human body’s temperature regulation; the exposure to the severely psychotic individuals was intolerable; the mental health care provided to inmates was “grossly inadequate”; and the isolation of death row, combined with the conditions on it and the fact that its population are awaiting execution, would weaken even the strongest individual. In 2004, the US Court of Appeals “agree[d] that the conditions of inadequate mental health care… do present a risk of serious harm to the inmates' mental and physical health. Again, the obvious and pervasive nature of these conditions supports the… conclusion that [Mississippi Department of Correction] officials displayed a deliberate indifference to these conditions.” While the authorities have recently improved the environmental conditions on death row following the lawsuit brought against them, there has been an ongoing struggle to ensure adequate medical and mental health care."

A long time ago, I wrote a long letter to the Warden of the Mississippi state penitentiary at the time, Don Cabana, who supervised the execution of Edward Johnson. The steps leading up to his execution were shown in the documentary 'Fourteen days in May.' I urged him to turn against the death penalty, giving reasons. Don Cabana did turn against the death penalty, although it's very unlikely that my letter had anything to do with his decision. Since then, he's spoken against it. His change of heart is recorded in his book 'Confessions of an Executioner.'