Lichfield Cathedral

Above, Richard Neile, Bishop of Lichfield. The Bishop, King James

(best known for the translation of the Bible which he sponsored, the 'King

James Bible') and others in the Church were determined that Edward Wightman

should be burned alive for heresy, and Edward Wightman was burned alive, in

1612.

More on this hideous episode, one episode amongst a vast number of

other episodes, in the second column of my page

Billingsgate:

Blasphemy, Heresy,

Witchcraft, Burning to Death. King James and the King James Bible

(Authorized Version). Bible-based dotrine and Bible-based barbarity. The

Lichfield Connection.

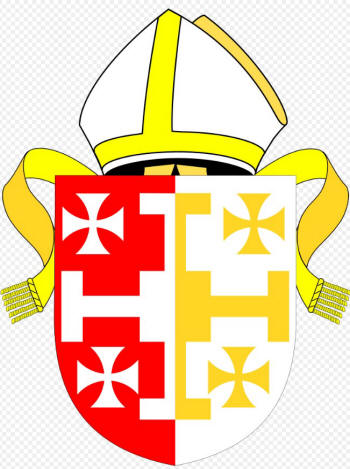

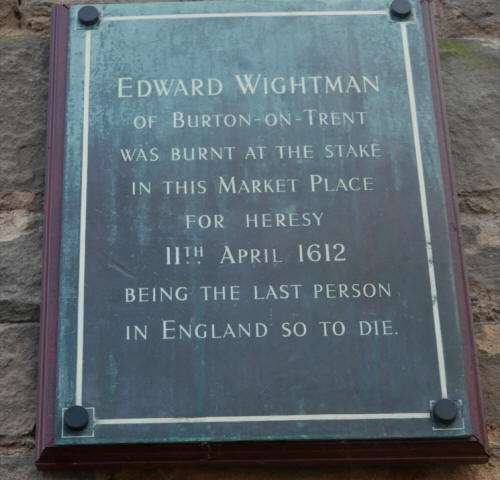

Above, plaque in the Market Place, on a wall of St Mary's Church, a

Church no longer, now used by 'The Hub at St Mary's,' which describes itself

as a 'creative space ... '

The plaque is on a wall, near to the entrance to the 'creative space' but

well above head height. It wouldn't be noticed by most of the people who go

to the Market Place. The plaque should surely have a much more prominent

place. It belongs to the history of Lichield, and the event commemorated has

significance which goes well beyond Lichfield. It has national, in fact,

international importance in important aspects of history: humanitarian

history and the history of free expression. Edward Wightman had make known

his opposition to the doctrine of the Trinity, amongst the other 'heresies'

which led to his being burnt alive.

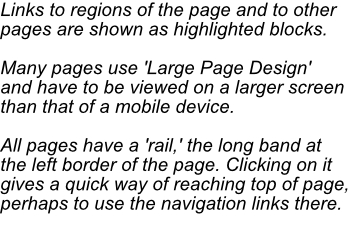

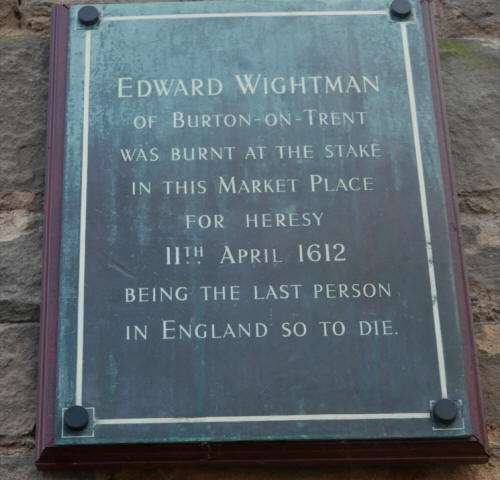

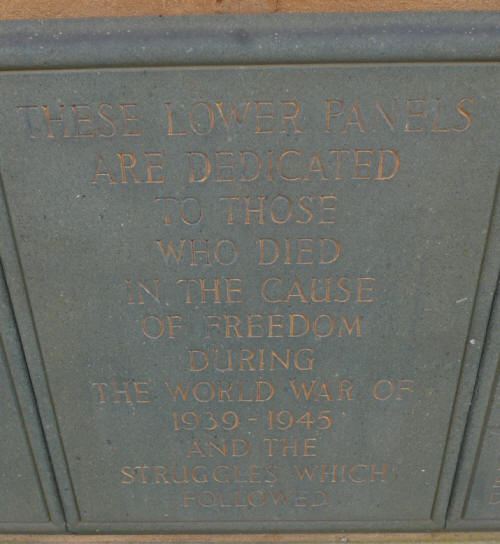

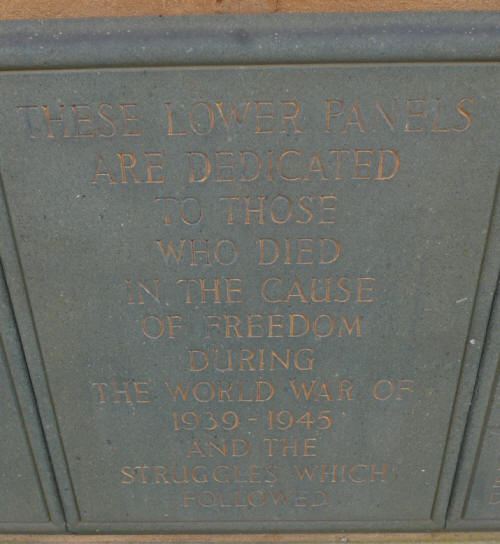

Above, a view of the War Memorial, of Portland stone, in the Garden

of Remembrance, Lichfield, a beautiful, evocative and harmonious place. This

photograph and the photograph below taken by me.

The War Memorial was constructed after the First World War to

commemorate those who fell in the conflict. Other panels were added to

commemorate those who fell in the Second World War and other conflicts. The

wording on the panel shown in the image above:

'These lower panels are dedicated to those who died in the cause of

freedom during the World War of 1939 - 1945 and the struggles which

followed.'

The linkages between aesthetic history and ethical history (which

includes humanitarian history and the history of freedom of expression) are

many. The contrasts between aesthetic history and ethical history have often

been ignored.

The Garden of Remembrance and the War Memorial show aesthetic

strengths in conjunction with very strong ethical strengths, but often,

there is lack of linkage, disproportion, grotesque disproportion.

Buildings and places which are aesthetically outstanding have

often been - still are - ethically poor, or much worse than that. Lacklustre

buildings and places may be ethically outstanding or ethically lacklustre or

ethically poor, or much worse than that. There's a similar range of

possibilities in the case of ugly buildings and places.

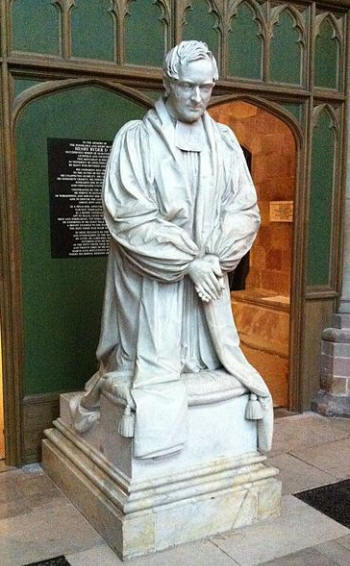

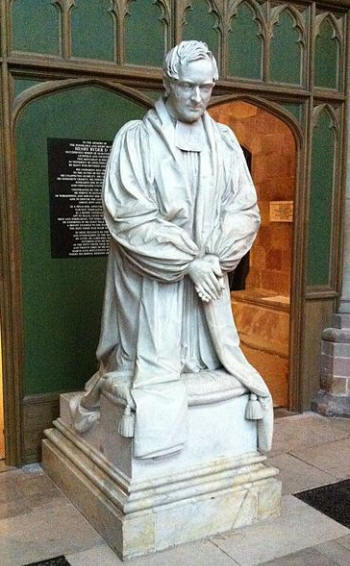

This is a statue of Henry Ryder, an evangelical Bishop of Lichfield

and Coventry between 1824 and 1836. The statue is surely lacklustre, an

example from the vast mass of commonplace statuary to be found in Churches

and Cathedrals which fails to achieve aesthetic distinction.

This is a statue of 'St' Chad, outside Lichfield Cathedral.

Architecture and building are strong interests of mine. Now, my main

preoccupation is vernacular architecture, particularly the vernacular

architecture of the South Yorkshire and Derbyshire Pennines, and above all,

the farm buildings and other buildings with stone walls and stone roof tiles

of the region. But I still have a strong interest in bigger, grander

buildings.

Many years ago, I used to include parish churches and

cathedrals in what could be called 'study visits' outside the area. Two of

the books I used, and still have, are 'English Parish Churches' by Graham

Hutton and Olive Cook and 'The Cathedrals of England' by Alec

Clifton-Taylor.

'English Parish Churches' has a very interesting

section 'On photographing cathedrals and parish churches' by Edwin Smith.

His experiences have similarities with my own, as well as significant

differences. My practice was very different. I never took photographs. I've

an aversion to relying upon the technology of photography. My emphasis is

and always has been upon the experience but since I started this Website, my

practice has changed. I"ve taken many, many photographs but almost always,

simply to provide illustrations for the site. I still emphasize the

experience rather than the record of the experience.

Alec

Clifton-Taylor was a wide-ranging writer on architecture and building,

including building stone. His view of the cathedrals was grounded in immense

knowledge and strong aesthetic values but my view of aesthetics is tempered

by other considerations.

Extracts from the section at the end of 'The

Cathedrals of England:, 'Visiting the Cathedrals: Summaries and Plans.'

Extracts from the summary of Lichfield Cathedral and its place in

the cathedrals of England:

'Leaving aside the parish-church

cathedrals, the four modern Anglican buildings ... and all those erected

since the eighteen-thirties by the Roman Catholic Catholics, England has

twenty-six cathedrals, of which, very conveniently, exactly half are of the

first rank.' He doesn't place Lichfield Cathedral in the list of cathedrals

'of the first rank.'

'Lichfield

At one time a

cathedral of surpassing charm, not all of which has evaporated, despite

restorations rendered necessary both by serious damage in the Civil War and

by the friability of the local red sandstone. The building is chiefly known

for its three stone spires, the Ladies of the Vale, the only English

cathedral to have these. Elaborate front with a profusion of platitudinous

Victorian sculpture ... The interior possesses in full measure the linear

richness so characteristic of English Gothic, yet wears an inescapably

Victorian air.'

He gives fuller comments on the successes and

weaknesses of the design in the main text. On some weaknesses:

'Of

the great display of Decorated sculpture on the west front of Lichfield

virtually nothing survives. All the statues, except five high up on the

north-west tower, are Victorian, and might pass as an advertisement for the

local hairdresser, every little wisp of hair on every figure having been

carefully 'set' in a fussy little curl.'

On the admixture of (purely

aesthetic) strengths and weaknesses in just one aspect of the building, the

West front:

' ... it turns out to be yet another example of the

screen type of front. The horizontal disposition is clear and good: the

tiers of figures under canopies are even carried round the octagonal

corner-turrets. The vertical articulation on the other hand, in contrast to

Wells, is very weak: about half-way down, the towers lose their identity

altogether.'

Throughout, Alec Clifton-Taylor's aesthetic standards

are exacting but very perceptive. Here, he writes about York Minster, which

is one of the cathedrals 'of the first rank:'

From the summary:

'Interior broad and lofty, yet lacking in magic: unfortunately, none of the

main vault is of stone ... York is famous for its stained glass; none of it

is of the very highest quality, but there is far more mediaeval glass here

than in any other English church, and its marked superiority to nearly all

Victorian and more recent glass will be apparent at once.'

Extract

from the main text, again on York Minster:

'This nave is the most

imposing example of the Decorated style in England, but not the loveliest.

The primary defect, once again, resides in the proportions ... York nave is

yet another English Gothic building which is too broad for its height ... In

other ways, too, this nave can be seen to fall short of the highest

standards of its brilliant period.'